Estimated read time: 3-4 minutes

- The U.S. reports more measles cases in 2025 than in all of 2024.

- Texas outbreak contributes most, with cases confirmed in 14 states.

- Utah pathologist Dr. Ben Bradley warns of long-term effects, including immune amnesia and neurological conditions.

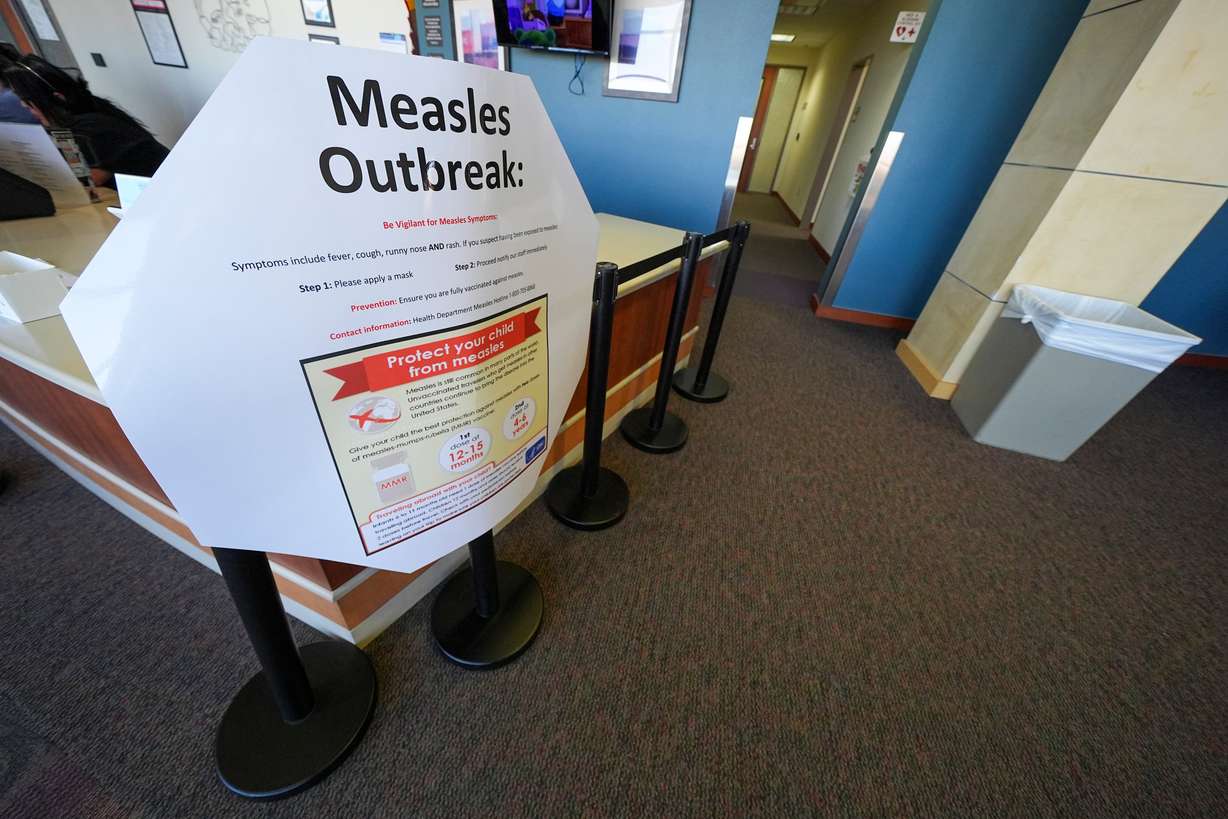

SALT LAKE CITY — The U.S. now has more measles cases than were recorded in all of 2024, making the early tally of 2025 second only to the 2019 record tally in recent history.

While most of the cases are part of the Texas outbreak, cases have now been confirmed in 14 states: Alaska, California, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Texas, Vermont and Washington.

The count includes only confirmed cases, per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention , which notes probable cases in other jurisdictions.

Two children have died, one with measles as the official cause of death and the other as a probable cause of death that's under investigation. In both cases, measles was confirmed.

Thursday, Utah pathologist Dr. Ben Bradley, medical director of virology of Salt Lake City-based ARUP Laboratories, on a national briefing warned that the full effect of measles might not be seen for years, as a rare complication can appear even a decade after someone apparently recovers from the virus. Bradley is also an assistant professor in the pathology department at the University of Utah.

The briefing sponsored by the College of American Pathologists, is titled "Measles Reemergence and How it Becomes Deadly."

Not really entirely gone

Measles was officially eradicated in the U.S. in the year 2000, thanks in large part to "strong public health programs both nationally and in the states" that contributed to controlling the highly infectious virus," said Dr. Donald Karcher, president of the college and a professor at the George Washington University Medical Center in Washington, DC., during the briefing.

Bradley noted a potential for serious complications in the form of either severe pneumonia that leads to respiratory failure and death, or acute encephalitis, where inflammation in the brain can be deadly. He said that the virus can infect children and wipe out their immune system's antibodies against previous illnesses, which some call "immune amnesia."

Said Bradley, "They get lower antibodies against previous infections." And their immune systems can be weak for longer than just during the acute infection period, too.

The other complication, which as noted is very rare, is called sub acute sclerosing panencephalitis or SSP, which he described as "a progressive degenerative neurological condition that is uniformly fatal. Because it can happen about 10 years after the virus infection, that means "the virus is no longer present in the person's system but is still causing severe disease at a community level."

He also noted that babies are vulnerable to measles because they are too little to have vaccines.

"What I want to stress is this isn't just a one-time respiratory illness that comes and goes. There are many downstream implications from this infection both to the individual and to the community," said Bradley.

Bradley said even well-vaccinated communities will have pockets that aren't immune. "You know when you have a large population and a very diverse population, there's risk that you can have that kind of tinderbox effect where someone comes in and causes big spread within a community."

He noted that vitamin A can be a supportive measure that can diminish mortality in children with measles, but does not prevent measles infection. And self-dosing can be dangerous, as well, because too much is toxic.

Measles by the numbers

The CDC surveillance count Friday reported that more than a third of the cases this year involve children younger than 5, while 42% were children ages 5 to 19. In 21% of cases, the person with measles is 20 or older. And in 3% cases, age is not known.

Fifty of the 301 people with measles this year have been hospitalized; the age group with highest hospitalization are those under 5 years of age (27%).

CDC reported that the majority of the 2025 measles cases involve people who either have not received the measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine or with unknown vaccination status. Three percent received one dose of the vaccine and 2% received both MMR vaccine doses. The vaccine is considered at least 95% effective at preventing someone from getting measles.