Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

- Chewing hard materials like wood may boost brain antioxidants and cognitive function, a study finds.

- A study found wood chewers had higher glutathione levels, improving memory function.

- Researchers caution about wood safety; hard foods like raw carrots may offer similar benefits.

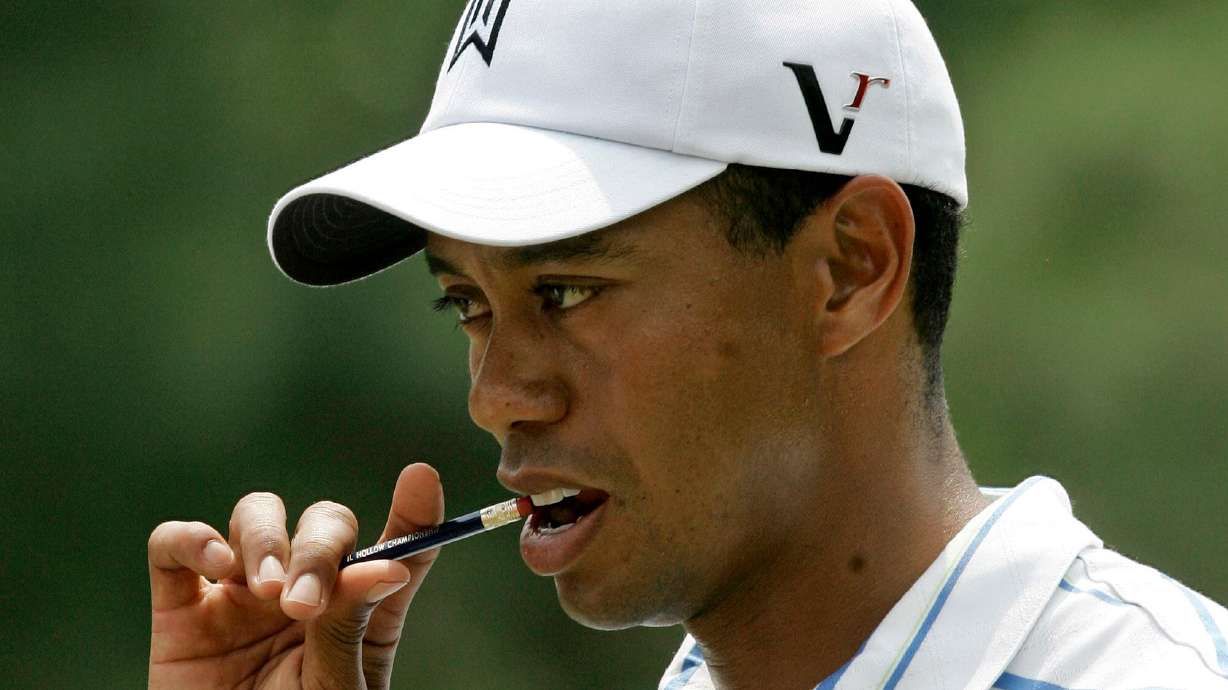

SALT LAKE CITY — If you've been knocking on wood hoping that your cognitive skills will stay sharp your whole life, you might consider chewing that wood instead.

A new study in the journal Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience found that chewing on hard material — raw carrots and other hard actual foods likely count — can boost brain antioxidants and improve cognitive function.

That chewing helps brain function is not a surprise. Chewing has long been known to increase blood flow in the brain, which is why some people swear by chewing gum while doing memory tasks. What may be surprising is that wood and other hard materials appear to make a bigger difference.

The researchers, from Kyungpook National University in South Korea and Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Tennessee, theorized that chewing hard substances raises the level of glutathione, which in turn helps memory and cognitive function.

The study design

To find out, researchers recruited 52 university students in Korea, sorted them into a gum-chewing group and a wood-chewing group after making sure they matched up in terms of age, gender, socioeconomics and other factors like health and education, then had them chew. Sure enough, chewing raised glutathione levels in the anterior cingulate cortex — the part of the brain they studied — but markedly more so among those who chewed on wood. The concentration was "positively correlated with memory function."

They used tongue depressors, similar to popsicle sticks, for the wood. And to make sure the difference wasn't in chewing style, each participant had his or her head stabilized in a fixation device. They all chewed on the right molar region at a specific speed, chewing for 30 seconds, then resting for 30 seconds, for a total of five minutes.

Before and after the chewing, the researchers used a magnetic resonance spectroscopy brain scan to measure levels of glutathione in the target area of the brain. The anterior cingulate cortex is important for thinking and cognitive control, they said.

Both before and after, the chewers were administered cognitive tests that look at memory, attention, language and visual-spatial performance. Post-chew, the wood chewers did better. They didn't find a change in memory performance in those who chewed gum.

Researchers concluded that chewing hard materials may protect the brain from oxidative stress.

"Chewing hard materials may effectively remove the reactive oxygen species in the brain and thus stimulate brain cells to improve the brain cognitive function," the study reported. "Furthermore, this finding may be particularly relevant for elderly individuals, as (glutathione) deficiency contributes to oxidative stress, which is implicated in aging and the pathogenesis of many neurodegenerative diseases."

As PsyPost notes of the findings, "Oxidative stress is essentially damage to brain cells caused by harmful molecules called reactive oxygen species. This kind of damage is thought to play a significant role in the decline of brain function as we age. The brain is especially vulnerable to oxidative stress because it uses a lot of oxygen and contains fats that are easily damaged. To protect itself, the brain uses antioxidants, and one of the most important is glutathione."

Glutathione neutralizes harmful reactive oxygen species.

Study limitations

There are some limitations to the findings, researchers noted. For one thing, the study participants were all 20 to 30 years old and it was a convenience sampling, which means they used as participants those who were handy. More study would need to be done to validate findings in different age groups. And it was a small study, which would need to be expanded, per the researchers.

They also noted that they focused on one area of the brain and the findings might not hold true in other regions. And they pointed out that all wood and gum are not created equal in terms of how hard or soft they are or what their texture is like. The researchers said they believe that chewing force could matter, but were not able to measure it for the study.

Still, "since there are currently no drugs or established practices for boosting brain (glutathione) levels, our findings suggest that chewing moderately hard material could serve as an effective practice for increasing (glutathione) levels in the brain. Based on these results, consuming harder foods might prove more effective in enhancing brain antioxidant defenses through elevated (glutathione) levels."

Should you chew wood?

The study could represent a change in thinking. After all, lignophagia — chewing wood — has been considered abnormal for humans, though beavers and horses do it quite often.

If you swallow wood, it's a form of pica, which the Cleveland Clinic defines as a "mental health condition where people compulsively swallow non-food items."

Certainly not all wood is safe. Some plants are toxic. Lots of wood products have been treated with chemicals and insecticides, so those aren't a good idea, either. Wood could be hard on teeth and with some wood there'd certainly be the risk of slivers or splinters.

There's also some risk from bacteria.

As the researchers noted, however, hard foods like raw carrots could provide the same effect found in the study. And chewing food thoroughly has pretty universally been considered good.