Estimated read time: 6-7 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

- A spectacular meteor shower was witnessed the night of Nov. 12, 1833, by many, including early Latter-day Saints.

- The meteors were interpreted by some as a divine sign, aligning with biblical prophecies.

- Despite their hardships, the Saints found hope in the celestial display, contrasting with the fear it inspired in others.

On the night of Nov. 12, 1833, Parley Pratt went to sleep under a clear sky. It had been raining for days on the Missouri River bottoms near Jackson County, Missouri, where Pratt and his fellow refugees lay their heads, weary from cold, rain and fear.

However, whatever shut-eye Pratt managed was interrupted by another type of downpour — not of rain or snow, but of stars.

"About two o'clock the next morning, we were called up by the cry of signs in the heavens," Pratt wrote in his autobiography, "The Autobiography of Parley Parker Pratt," which was published in 1874 after he died.

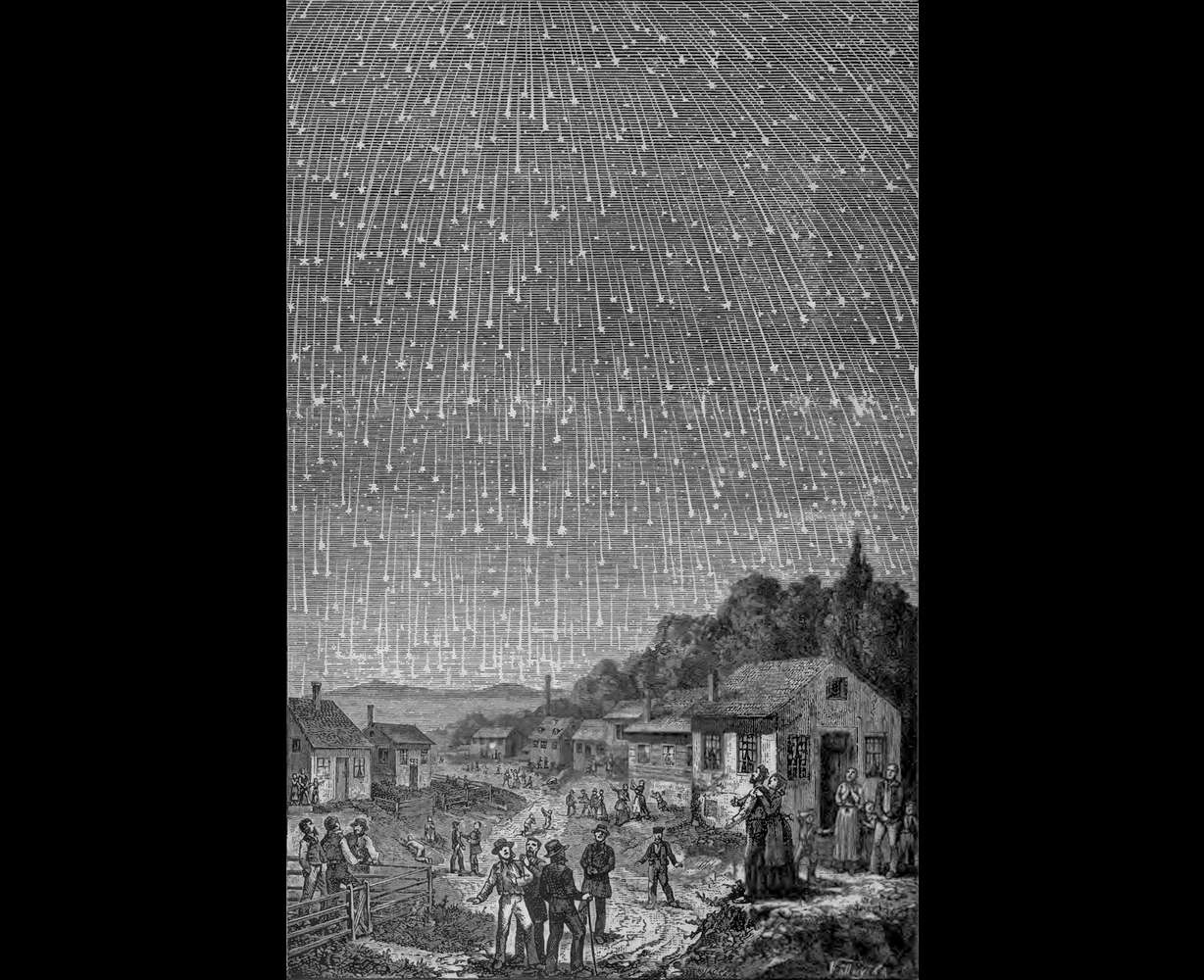

Pratt and the others in the camp gaped in amazement as thousands of meteors filled the sky. They fell like "splendid fireworks," Pratt wrote, "trailing long trains of light. At a glance, there seemed to be no order to the chaos above them, with the thousands of lights dashing towards all points of the compass.

"(It seemed) as if every star in the broad expanse had been hurled from its course and sent lawless through the wilds of ether," he recalled.

Young Eliza Partridge, daughter of then-Bishop Edward Partridge, was also in the camp and recalled how the meteors "came down as thick as snowflakes." Her father likewise attested this "extraordinary phenomenon … streamed down almost as thick as rain."

The early members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints stood captivated as these meteors exploded overhead. Sleep was apparently out of the question; they watched all night until the sun obscured the meteors, rising on a brighter day.

The early morning hours of Nov. 13, 1833, would be remembered for generations as "The Night the Stars Fell."

Across the United States that night, the sky erupted in a deluge of meteors. They filled the sky with a continuous barrage of light so bright that if they didn't wake a person directly, a gobsmacked neighbor likely did, according to various accounts. People from all walks of life witnessed the storm, including a young Abraham Lincoln and then-enslaved Fredrick Douglass. While some delighted in the incredible sight, others feared it portended Judgment Day.

We now know this was an outburst of the Leonid Meteor Shower, which occurs every November and usually produces about a dozen meteors per hour.

However, the 1833 storm unleashed thousands of meteors a minute — due to a large "meteoritic swarm" of particles left behind from the comet Tempel-Tuttle, according to Mark Littman, a science writer and author of "The Heavens on Fire." Tempel-Tuttle orbits the sun about every 33 years, leaving behind a larger trail of debris for Earth to plow into, which is why the Leonids erupted in an outburst over South America in 1799 and why scientists correctly predicted its return 33 years later in 1866.

None of this was known in 1833, however, when scientists still thought meteors were part of the weather.

It would all change in 1833 when a Yale professor capitalized on the sheer number of both meteors and eyewitness accounts to begin to winnow out the true nature of meteors, Littman wrote.

But, while the world was on the cusp of this scientific revolution, many eyewitnesses interpreted the storm through a religious lens, as it bore an uncanny resemblance to prophecies written in scripture: "And the stars of heaven fell unto the earth, even as a fig tree casteth her untimely figs," the Apostle John wrote about the "signs of the times" in the book of Revelation in the King James Version of the Bible.

For many who made the connection between the Biblical imagery and the view outside their bedroom window that morning in 1833, this arresting sight caused panic and fear, W.T. Dameron recounted to the Moberly, Missouri Monitor in 1930 the pandemonium the storm caused in his father's family: "Mother opened the door to see what it meant. She was horrified, threw up her hands and cried, 'The world's on fire, the day of judgment has come,' and she commenced praying."

The Saints in Jackson County likewise recognized the spiritual significance of the storm; however, as they watched the stars fall that night, they rejoiced.

"Every heart was filled with joy at this majestic display of signs and wonders, showing the near approach of the coming of the son of God," Pratt wrote.

Members of the then Church of Christ (later named The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) had been gathering in Jackson County, Missouri, after the Prophet Joseph Smith's revelatory declaration in 1831 that it was to be the "place for the city of Zion." It would be a place where they could "prepare for the second coming of Jesus Christ," according to the Joseph Smith Papers.

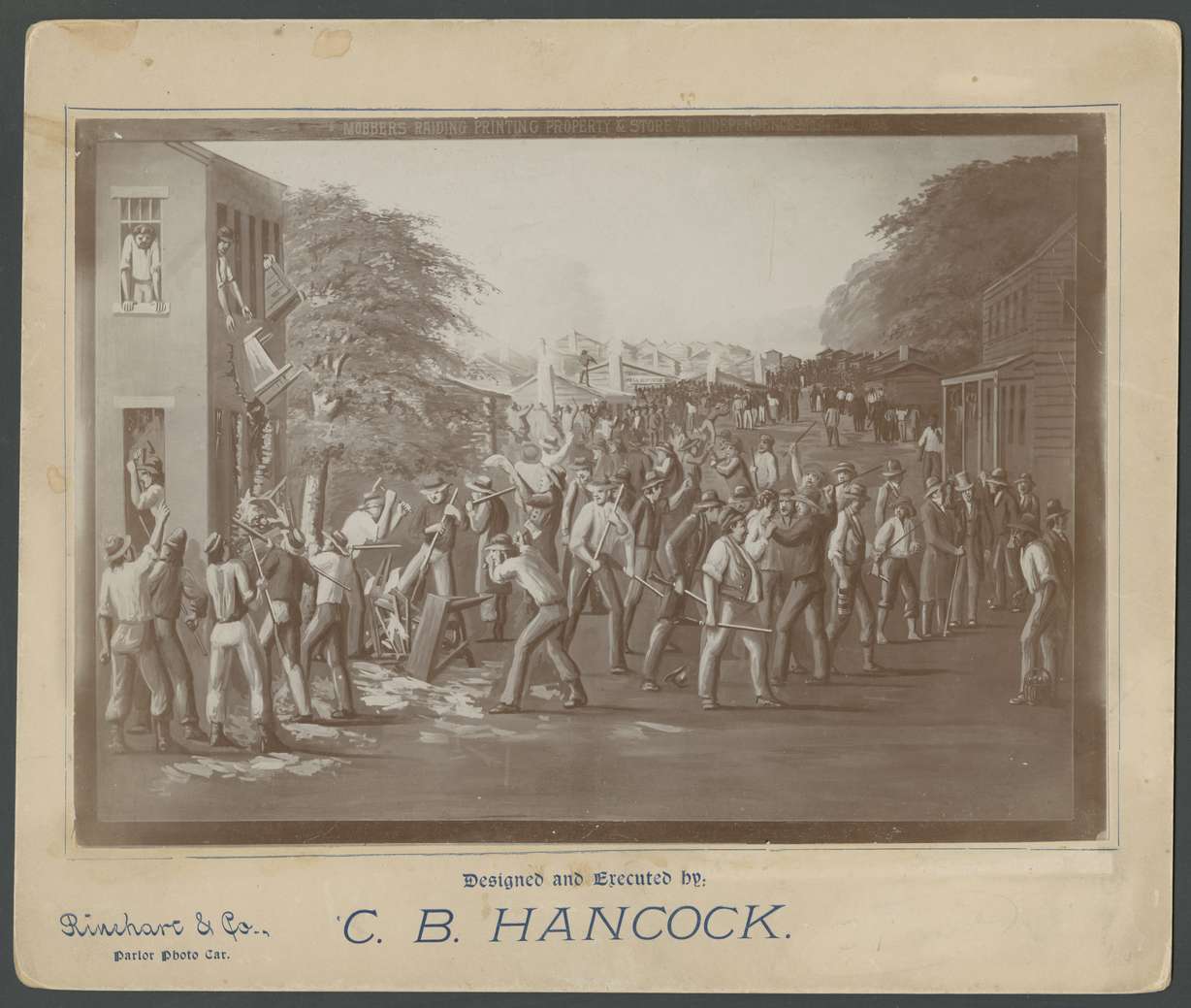

Latter-day Saint Historian Bruce A. Van Orden, in a biography of W. W. Phelps, wrote that this belief caused tension between the Saints and their "gentile" neighbors. These tensions, which Van Orden writes were fed by other issues, as well, erupted in violence in the summer of 1833 when a mob formed by these original settlers ransacked businesses and abused church members. In November, the mob finally drove them from their homes.

"It is a horrible time," Missouri church leader William W. Phelps wrote to Joseph Smith on Nov. 7, according to historical accounts. "Women and children are fleeing, or preparing to, in all directions."

Pratt had just returned to the camp on the Clay County side of the river and was amazed at the flurry of activity. He helped cut cottonwood trees to build makeshift shelters for the homeless, all "while rain descended in torrents," he wrote.

Of the conditions in the camp, one refugee wrote, "Log heaps were our parlor stoves and the cold, wet ground our velvet carpets, and the crying of little children our pianoforte."

Eliza Partridge remembered being "very cold and uncomfortable," this being her first experience sleeping outdoors.

But she also remembered the majesty of the storm.

"It was here. I saw the falling of the stars," she wrote.

While the Saints rejoiced at what they saw, their enemies "were very much frightened," wrote Eliza Partridge. Josiah Gregg, a trader living in Independence at the time, corroborated this in his book "Commerce of the Prairies," writing that some in the mob wondered if this was "not a sign sent from heaven as a remonstrance for the injustice they had been guilty towards that chosen sect."

Edward Partridge received reports that meteors struck the ground in Independence, but since "the artillery and fireworks of heaven" did not rain down on their enemies, the bishop realized only another miracle could save his people.

"If we are delivered and permitted to return to our homes, it must be by the interposition of God, for we can see no prospect of help from (the) government," Phelps wrote to Smith after the storm.

God did not interpose; the Saints settled in other parts of the state, only to be expelled from Missouri completely in 1838.

Though the stars figuratively fell on the Jackson County Saints in 1833 — resulting in loss of property and dignity — the Leonid meteor storm quenched their fears in words that can be heard by Diantha Billings, the wife of one of Bishop Partridge's counselors, who wrote while her husband was helping families across the Missouri River.

Alone with her three children, she had looked up at the night sky filled with so much light, and said, "Praise God, the Lord is merciful to us."