Estimated read time: 5-6 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

- The U.S. bird flu outbreak has killed off millions of wild and farm birds since 2022.

- California declared a state of emergency due to the bird flu outbreak in cattle.

- Experts say current human impact remains low, but warn that larger concerns are possible if the spread mutates in other animals.

SALT LAKE CITY — Dr. Ben Bradley learned the importance of spaghetti models while growing up in southeast Louisiana and tracking hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico.

These meteorological models offer all the storm track possibilities and probabilities. Only time could tell, though, whether an incoming storm would decimate his family's property, completely missing it or partially impact them.

Bradley is now an assistant professor in the University of Utah's pathology department and director of virology at ARUP Laboratories, where he's tracking the latest epidemiological hurricane of sorts.

California declared a state of emergency on Wednesday over the highly pathogenic avian influenza — commonly referred to as bird flu — as it continues to spread through dairy cows in the state. Bird flu has also been detected in cows, chickens and turkeys on farms and in backyard flocks across Utah in recent months, forcing over 1 million birds to be culled in the state.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also announced this week a severe human case was detected in Louisiana, the first since the outbreak began in 2022.

These types of outbreaks, Bradley says, will continue to occur as long as there are wild birds and mammals on this planet, but he can't say how impactful this outbreak will be.

Related:

In short, this outbreak is still churning along the coast and the impact remains unclear. It could still spread to and remain in cattle herds next year, but it could also be an animal away from mutating into something more cumbersome.

"We're now in a situation where those events could be happening," Bradley said. "Putting a timeline on it is challenging to say, but we can say we're in a situation where we need to be alert to the possible threat of this."

Understanding the outbreak

Bird flu is a form of influenza A, explains Dr. Bobbi Pritt, a professor of laboratory medicine and pathology and chairwoman of clinical microbiology at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. It's an RNA virus that makes it "prone" to genetic mutations and many different variants and clades — or genotypes.

There have been many outbreaks in history. The primary clade outbreak in the U.S. started nearly three years ago in South Carolina and spread across the country, including to Utah, through wild birds.

By November 2022, over 50 million U.S. birds had either died from the virus or been killed. However, the virus never really stopped, only popping up in strong waves here and there. The CDC now estimates the number of dead birds has surpassed 120 million, most of which have been commercial poultry.

What we're facing with (the bird flu) is a very different landscape than COVID.

–Dr. Ben Bradley, U. Department of Pathology

But, among wild bird cases, it killed off a chunk of the endangered California condor flock in Utah and Arizona last year. Bird flu was also detected this month in multiple dead sparrows, starlings, doves and pigeons collected in Cache County, per U.S. Department of Agriculture data.

Bird flu in cattle became a concern after cases in Kansas, New Mexico and Texas earlier this year, prompting Utah to implement some restrictions. It's picked up in recent months, not only in California but also in dairy cattle in Cache County.

Human impacts, so far

The outbreak has had very low impacts on human public health up to now. The CDC reports 61 human cases in the U.S. and there has been no documented human-to-human spread of the bird flu.

Nearly all of the confirmed cases have resulted in minor symptoms. Bradley believes there are likely more cases out there, but he suspects they aren't reported because people are asymptomatic, symptoms are minor, or they don't have time to get tested.

He's also quick to point out it's nothing like the COVID-19 pandemic because there is better knowledge of the virus and its tendencies, better testing capacity and more time to prepare for wider impacts.

"What we're facing with (the bird flu) is a very different landscape than COVID," he said.

Experts are still dissecting information from the few cases available to decode, but it's unclear why the case in Louisiana — and a similar case in Canada last month — ended up being severe.

This year's flu shots offer protection against some influenza A strains, but there is only "hypothetical" evidence that bird flu is included in any of those protections, Pritt said.

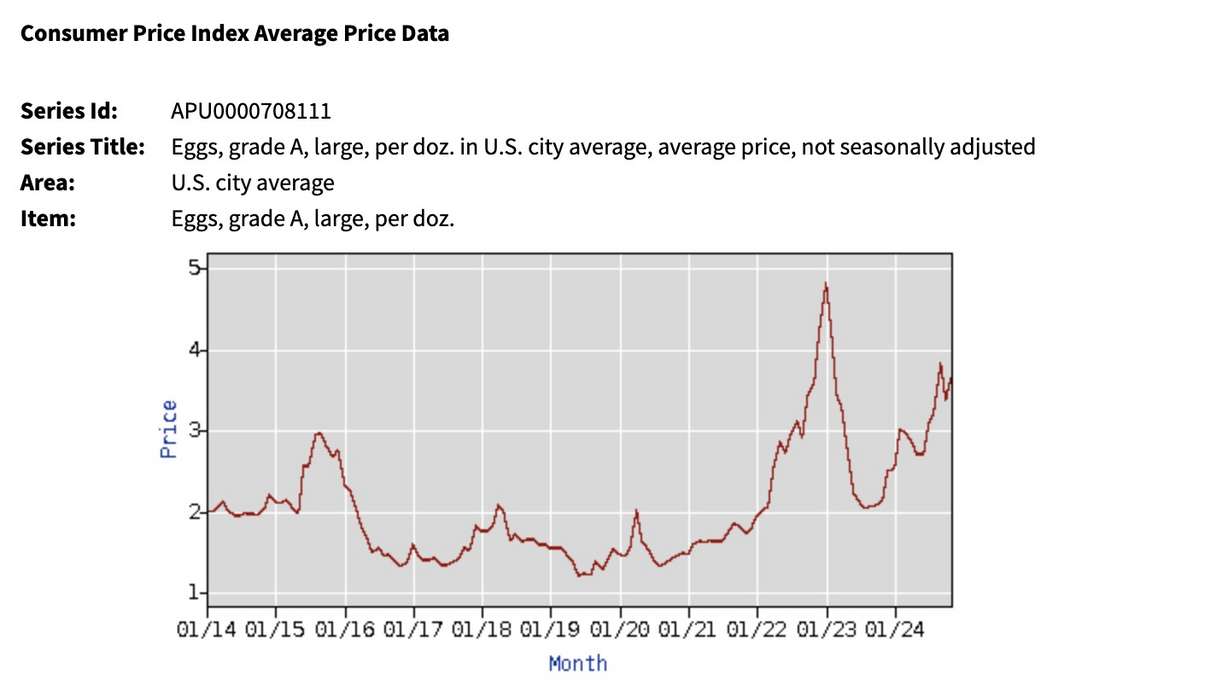

At this point, the largest widespread human impact might be on the wallet. Egg and chicken prices have soared in recent years — not just because of record inflation but because of factors like the bird flu. The virus has lowered poultry populations.

Why the concern?

Experts believe this outbreak might be getting more attention because of its timing in proximity to the COVID-19 pandemic, but it's also the largest of its kind.

There's still an opportunity the virus mutates in a mammal — such as cattle, cats and pigs — which would make it more transmissible to humans.

"The more virus you have out there, the more it's replicating (and) the more mutations could occur that would then make it more transmissible among humans," Pritt said.

Bradley said there are two trends he's tracking that could elevate his concern.

There have been a few cases without a clear link between humans and cattle, poultry or wild birds. That's a possible concern if it continues. Summertime spread is also potentially concerning because the flu generally dies off in the summer.

But, like those hurricane spaghetti models, he said it's something to keep an eye on for now.