Estimated read time: 3-4 minutes

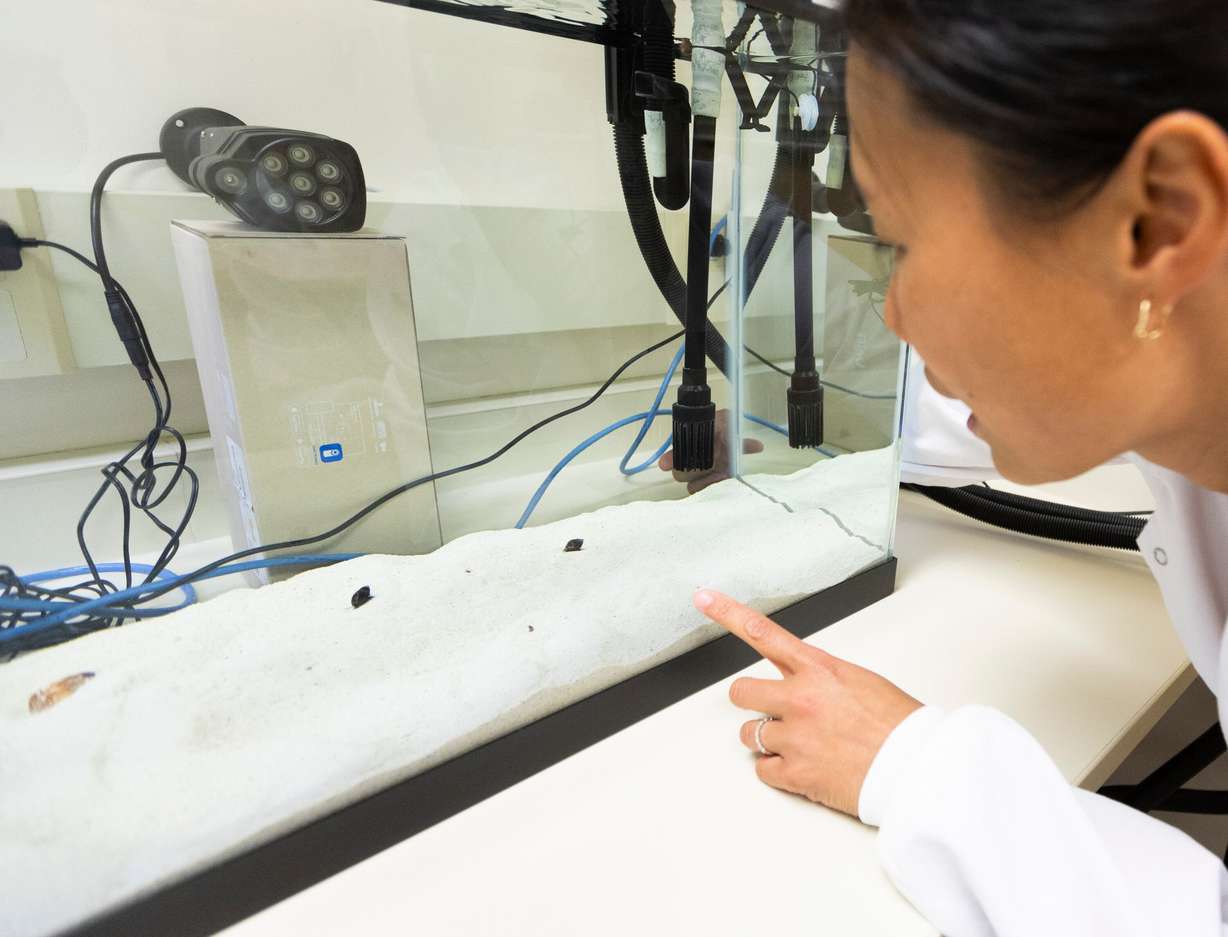

SALT LAKE CITY — The venom of geography cone snails may hold the key to developing better drugs for people with diabetes or hormone disorders.

The findings of an international research team led by University of Utah scientists just published in the peer reviewed journal Nature Communications suggest a component of the venom that the snails use to help hunt their prey mimics a human hormone called somatostatin, which regulates blood sugar levels and various hormones in the body.

According to Helena Safavi, associate professor of biochemistry in the University of Utah's Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine and the senior author on the study, venomous animals have, through evolution, fine-tuned venom components to hit a particular target in their prey and disrupt it.

"If you take one individual component out of the venom mixture and look at how it disrupts normal physiology, that pathway is often really relevant in disease," she said in a press release.

For medicinal chemists, "it's a bit of a shortcut."

In humans, somatostatin acts like a brake preventing the levels of blood sugar, various hormones and many other important molecules from rising dangerously high. The researchers found that the cone snail toxin called consomatin works similarly. However, it is more stable and specific than the human hormone, which makes it a promising blueprint for designing drugs.

The journal article describes it as a "stunning example of chemical mimicry."

Venomous animals have evolved diverse molecular mechanisms to incapacitate their prey and to defend against predators, the journal article states.

"Most venom components disrupt nervous, locomotor and cardiovascular systems or cause tissue damage. The discovery that certain fish-hunting cone snails use weaponized insulins to induce hypoglycemic shock in prey highlights a unique example of toxins targeting glucose homeostasis," the article states. Glucose homeostasis is the process by which the body maintains blood sugar levels within a narrow range.

In addition to insulins, geography cone snails, deadly fish hunters, use a selective somatostatin receptor 2 agonist that blocks the release of the insulin-counteracting hormone glucagon, thereby exacerbating insulin-induced hypoglycemia in its prey. Hypoglycemia is a condition in which your blood sugar level is lower than the standard range.

"We think the cone snail developed this highly selective toxin to work together with the insulin-like toxin to bring down blood glucose to a really low level," said Ho Yan Yeung, a postdoctoral researcher in biochemistry and the first author of the study.

The fact that multiple parts of the cone snail's venom target blood sugar regulation hints that the venom could include many other molecules that do similar things.

"There could potentially be other toxins that have glucose-regulating properties, too," Yeung said.

Cone snails as a group are found in tropical and subtropical oceans around the globe, but most species including the geography cone snail are found in the Indo-Pacific.

It appears the cone snail is able to outperform the human chemists at drug design but snails have evolutionary time on their side, Safavi said.

"We've been trying to do medicinal chemistry and drug development for a few hundred years, sometimes badly," she said. "Cone snails have had a lot of time to do it really well."

Or, as Yeung explains, "Cone snails are just really good chemists."

The research, conducted in collaboration with the University of Copenhagen, was published Aug. 20 under the title "Fish-hunting cone snail disrupts prey's glucose homeostasis with weaponized mimetics of somatostatin and insulin."