Estimated read time: 5-6 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — It's hard to spot the small, red brick Japanese Church of Christ in downtown Salt Lake City. But in the shadow of the massive Delta Center, tucked behind the vacant Struve Building and all but surrounded by a parking garage, the century-old chapel stands as a testament to a mostly forgotten community.

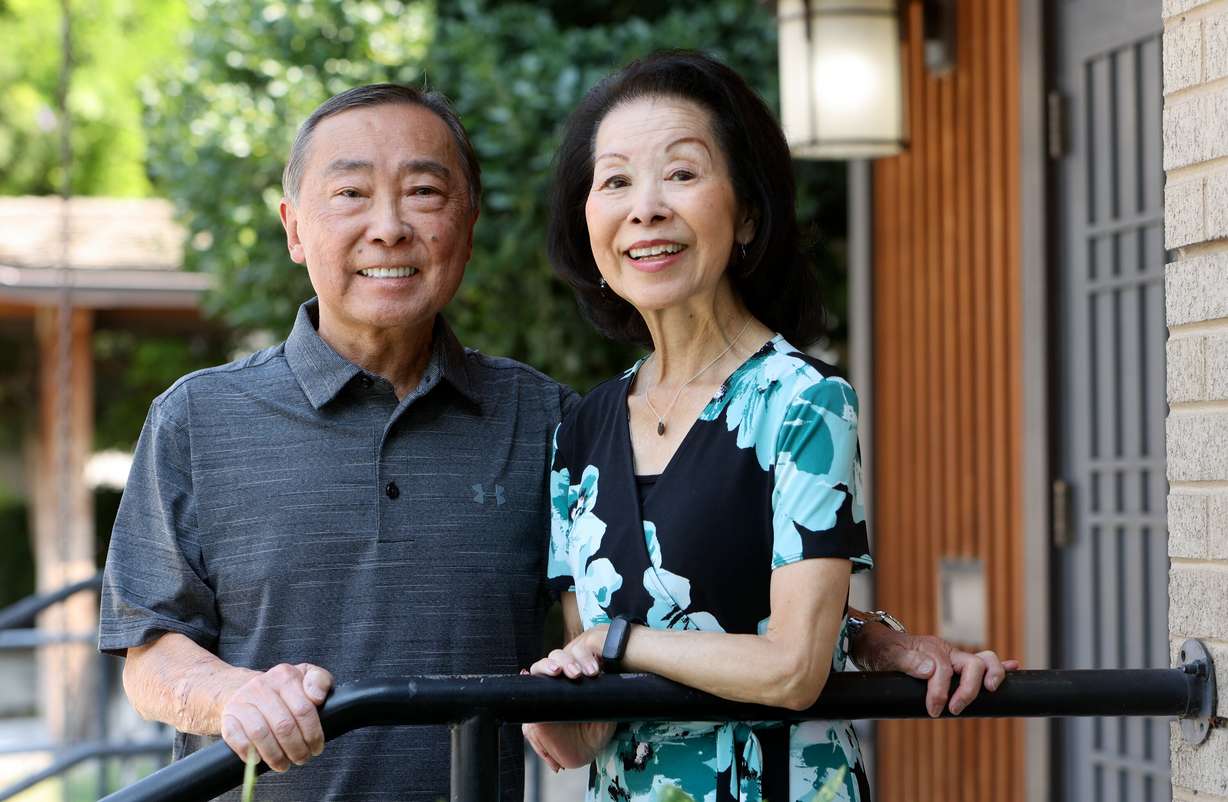

Meeting in the adjacent fellowship hall because the church is undergoing renovation, about 30 people on a recent Sunday morning worshipped in word and song. A large, open Bible, a cross and two lit candles sat on a wooden table lugged over from the church. Strands of origami cranes hung in the windows, while longtime member Ron Nishijima's colorful paintings adorned the wall. Lantern-shaped light fixtures dangled overhead.

Guest pastor the Rev. Mike Clang delivered a sermon he titled "Do What?" on God commanding Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac. The congregation then stood for the doxology: "Praise God from whom all blessings flow," first in Japanese, then in English. Next came "prayers of the people." Those in need of help from above were listed on the program. The Rev. Clang read each name individually.

"PNC," he said, referring to the Pastor Nominating Committee, which is searching for a new permanent minister.

"Lord, in your mercy hear our prayer," the reverend and the congregation said.

"Japantown," he said.

"Lord, in your mercy hear our prayer," they recited again.

For the people who worship here, Japantown — what's left of it — needs divine intervention.

An ambitious new project threatens the future of the Japanese Church of Christ and the Salt Lake Buddhist Temple down the street, the sole remnants of what once was a thriving Japanese American community. The two buildings sit in the path of a plan to remake downtown Salt Lake City.

Smith Entertainment Group, which owns the Utah Jazz and the new Utah Hockey Club, intends to put $3 billion into a sports, entertainment, culture and convention district covering a three-block area east of the Delta Center.

The proposal includes reconfiguring the arena entrance to face east, pedestrian plazas, taking 300 West underground between 100 South and South Temple, and building one or more residential towers and a hotel. The project, which aims to better connect the east and west sides of downtown, could impact the Salt Palace Convention Center, Abravanel Hall, Utah Museum of Contemporary Art and Japantown Street.

The Japantown of yore is long gone. It's uncertain what the new development will bring.

"It really was a nice, warm community. The people were friendly. It was a gathering place," said 90-year-old Nishijima after church services. "Everybody was so kind to each other. I hope we can regain some semblance of what we had. But I don't know if that's possible."

Smith Entertainment Group has worked closely with the city and members of the Japanese American community who want to ensure Japantown isn't swallowed in the project and to recognize its cultural and historical significance.

The company has vowed to be sensitive to the "unique challenges" the churches face. Rolen Yoshinaga, a Salt Lake Buddhist Temple board member, said if done right, the project could be an asset not only for Salt Lake City but the two churches.

An enlivened Japantown Street, he said, would bring diversity to the district. He said Japanese Americans are cautiously optimistic that can happen.

When Japantown bustled

First-generation Japanese immigrants — Issei — started arriving in Utah in the late 1800s, mostly as railroad, mine and agricultural workers. By 1907, residences and businesses started to emerge from South Temple to 300 South and State Street to 700 West, the heart of the bustling community centered on 100 South between West Temple and 300 West.

Noodle houses, hotels, rooming and boarding houses, bath houses, variety stores and barber shops lined the street. The Intermountain Buddhist Church was established in 1912, and the Japanese Church of Christ in 1918 to meet religious, cultural and social needs.

Most Japanese lived in the area and, for some, living quarters were in the back rooms of businesses or above them. Children grew up with the sidewalk and alleys as their playground. They played kick-the-can and hide-and-seek on the dirt streets in the middle of the blocks.

Empty lots became softball fields, and the grassy islands in the wide city streets were ideal for football. The Buddhist Temple showed Japanese movies with English subtitles and Kabuki productions in the basement.

The community tripled in size during World War II with the voluntary evacuation of Japanese Americans from the West Coast. The migration alarmed state and local government leaders. The Utah Legislature hurriedly passed a law that barred Japanese from buying land in the state from 1943 to 1947.

Organizations and groups petitioned the city commission to stop issuing them business licenses. In spite of the opposition and discrimination, the number and kinds of businesses increased as they settled in Utah. Law offices, beauty salons, apartments, gas stations, produce companies, florists and nurseries, appliance and jewelry stores all opened their doors.

From its inception, Japantown, also known as Nihonmachi, meaning Japanese Town, was the gathering place for Issei, Nisei (second generation), and Sansei (third generation) in Salt Lake City. On any given day, they met at Aloha Fountain and the Pagoda restaurant, or ran into each other at California Market, Family Market, New Sunrise Fish Market and Sage Farm Market.

They mingled as their cars were gassed up and serviced at Tats Masuda's Uptown Service Station or Pee Wee's Conoco Service. In its heyday, an estimated 2,000 to 8,000 people lived in Japantown. It even had three newspapers at one point.