- Intermountain Children's Health launched a telestroke program for pediatric stroke patients to provide quick care in rural areas.

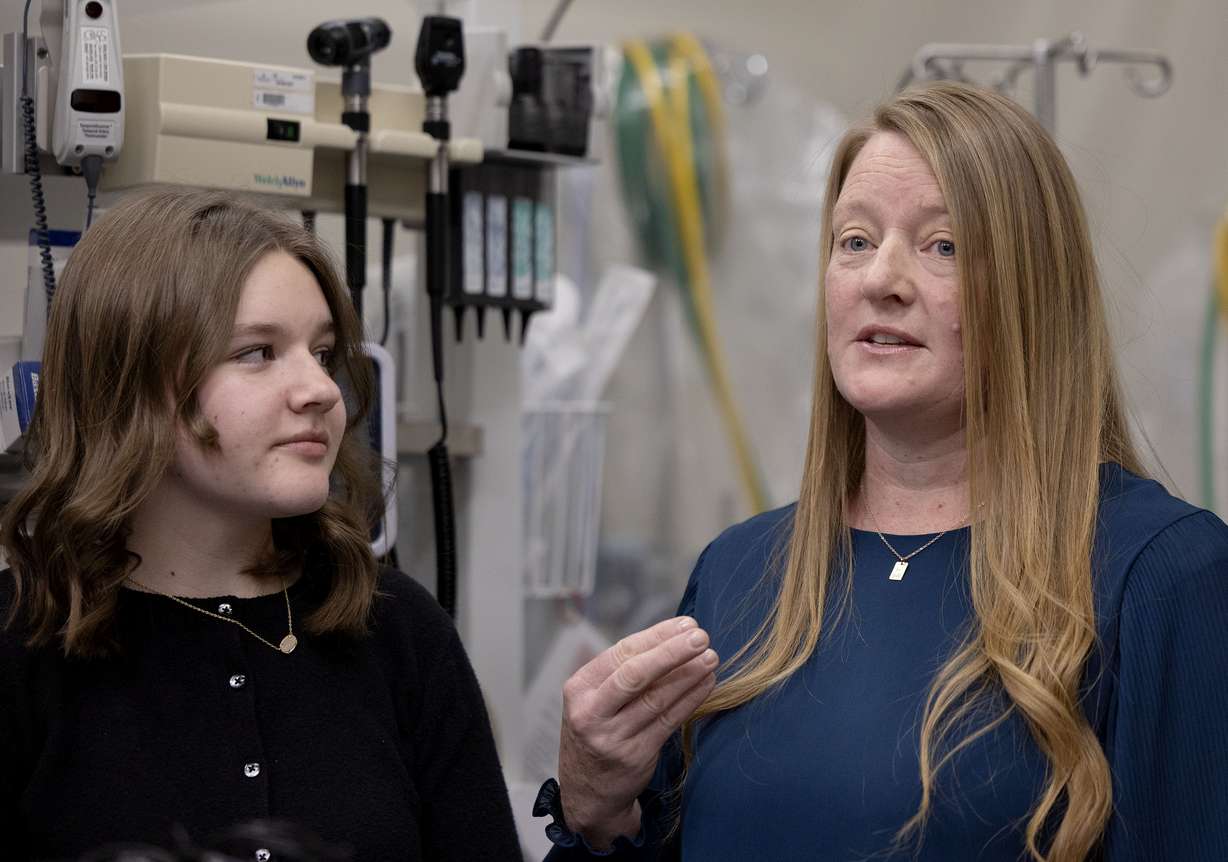

- A 14-year-old stroke patient talked about her experience recovering from a severe stroke.

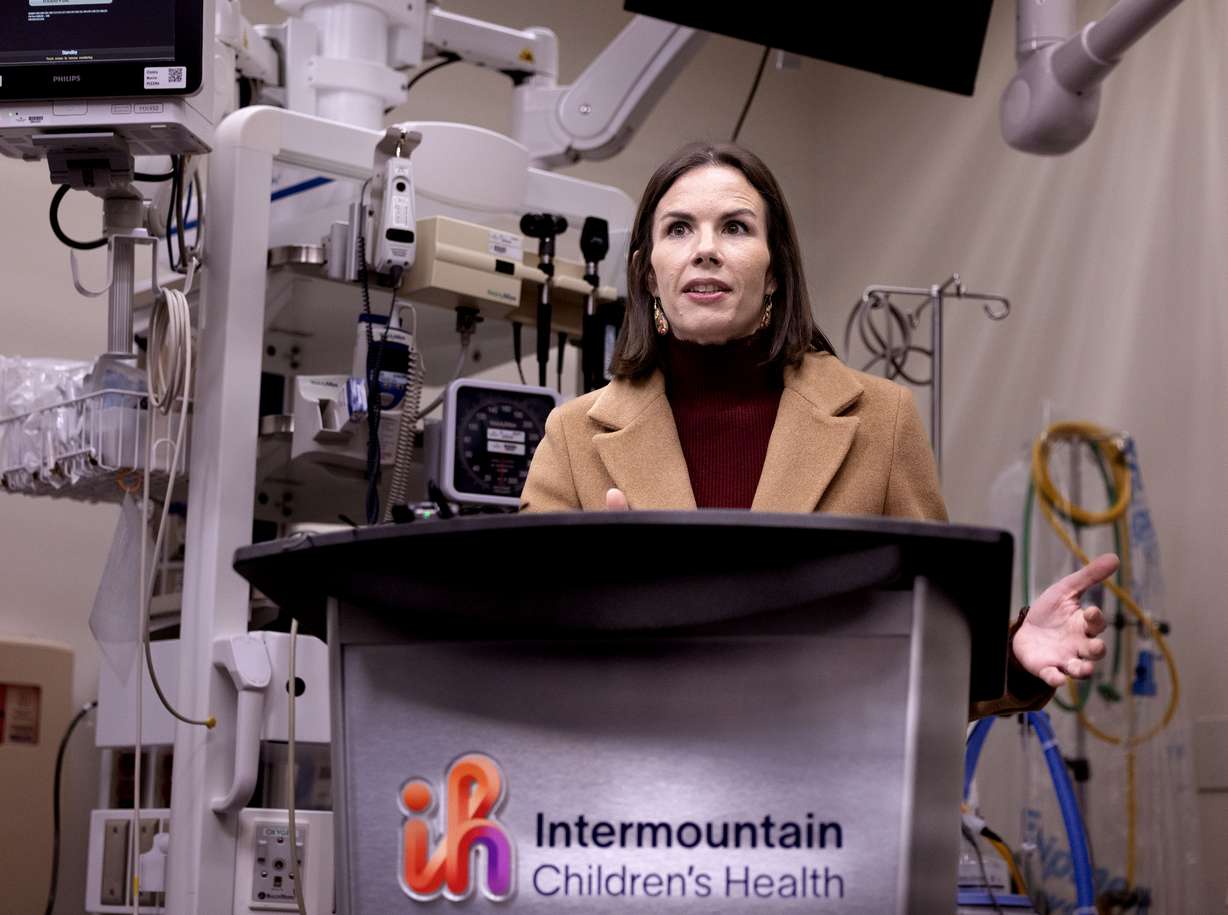

- Director Lisa Pabst emphasizes timely diagnosis to prevent long-term damage in children.

SALT LAKE CITY — Lucy Merrell, then an eighth-grade student, was getting ready for soccer practice when she felt a massive headache. She said she tried to lay down, but it wouldn't go away.

She became emotional Thursday as she recalled her mother getting help for what ended up being a severe stroke. Lucy called the experience a miracle and said she trusted her Heavenly Father would protect her.

"I'm so glad that I got another chance to be here," she said.

Lucy shared her story at a press event to spread awareness about childhood strokes and the new Intermountain Children's Health Telestroke Network — which it said is the "largest, most robust in the country."

Miracles

On April 8, 2024, Melanie Merrell said her daughter came to find her but was not walking normally; she seemed to be trying to point to her head and could not communicate.

"I thought to myself, 'Why am I seeing stroke symptoms?. Kids don't have strokes,'" she said.

Merrell said she knew time was of the essence. The symptoms starting at home before her daughter was at soccer practice was their "first miracle."

Her father, Randy Merrell, joined them at the trauma bay at American Fork Hospital. An intensive care unit nurse himself, he encouraged the doctor to consider a stroke. He said the doctor was resistant but contacted a doctor at Primary Children's Hospital and started connecting Lucy with the right treatments.

Melanie Merrell talked about the joy they experienced seeing small results during her daughter's two weeks in the hospital, such as lifting her arm and kicking her leg. Lucy initially called her parents numbers, because she had trouble with words. She said there were landmarks and "so many blessings."

Lucy loves to sing, and her mother recalled one moment when Lucy started singing along to a Taylor Swift song they had playing near her ear, getting the words and tune right.

Randy Merrell encouraged parents to be aware of stroke symptoms, as children can lose years of life from delayed care.

"Be willing to just take a step out there and say, 'I know it's not common, but maybe that's what's going on,' and just don't waste time. Just get them to that emergency room as quickly as you can because time is brain in this instance," he said.

His daughter didn't benefit from the telestroke program, which wasn't established yet, but he expressed gratitude for it.

"I think this will be a great thing for so many other places that are in rural areas," he said.

After speech and physical therapy, Lucy was able to start her next school year as planned. This year she went to New York with her high school choir. Now, she said she feels called to share her story.

"How can I stay quiet if it has seriously changed my life?" she said.

Telestroke program

Lisa Pabst, director of the pediatric stroke program at Primary Children's Hospital, said she often thinks of Lucy. She said her stroke in many cases would have led to a child not walking or talking at this point — but her family was able to identify it and push for quick treatment.

She said the focus of the telestroke program is to help children get to available treatments quickly. Every second without blood flow to the brain leads to dying brain cells.

The pediatric telestroke program allows a doctor like Pabst to get on camera and help a caregiver who may have never seen a pediatric stroke patient evaluate and treat the stroke as quickly as possible. It also includes meeting with doctors at each of the 24 hospitals the program is at throughout Utah and Idaho to teach them.

"Our goal is that they can get that same initial care as if they were here within the walls of Primary Children's Hospital," she said.

Pabst said the program helped 19 children during its first year, and they expect that number to rise as the program expands.

She hopes the system empowers providers to not be afraid of a stroke diagnosis but instead be afraid of missing the diagnosis, leading them to seek help more quickly. If it takes hours or a day before the stroke is identified, a child can have extensive, permanent damage.

"Most kids get better. ... But a lot of kids, unfortunately, are left with significant impairments in the long run," she said.

Childhood strokes

Pabst said she is "in awe" of Lucy and her story inspires their program.

"(Her story) really shows why recognizing a stroke quickly can change what's possible for recovery," she said.

Pabst said it was only in the 1990s that people began to realize kids were having strokes, and in the last 10 years, treatments used in adults were expanded to children. At the end of January, kids were first addressed in the guidelines provided by the American Stroke Association, which she called "a huge step forward."

She said stroke signs for children are similar to those in adults. They include: problems with balance, vision, a facial drop, arm weakness and slurred speech, but two additional symptoms to watch for in kids are seizures and headaches. She also said some of the typical stroke symptoms can appear more mild for children.

In children, strokes can be caused by heart problems, infections or blood vessel narrowing, which reduces blood to the brain, Pabst said.

Since children's brains are still developing, Pabst said they can be more resilient than adults, and therapy can be more effective.