- Utah's newborn screening now includes Hunter syndrome among 45 conditions tested.

- Early detection of Hunter syndrome can prevent irreversible organ damage and death.

- To be added to the test, conditions must affect newborns and there must be treatments available.

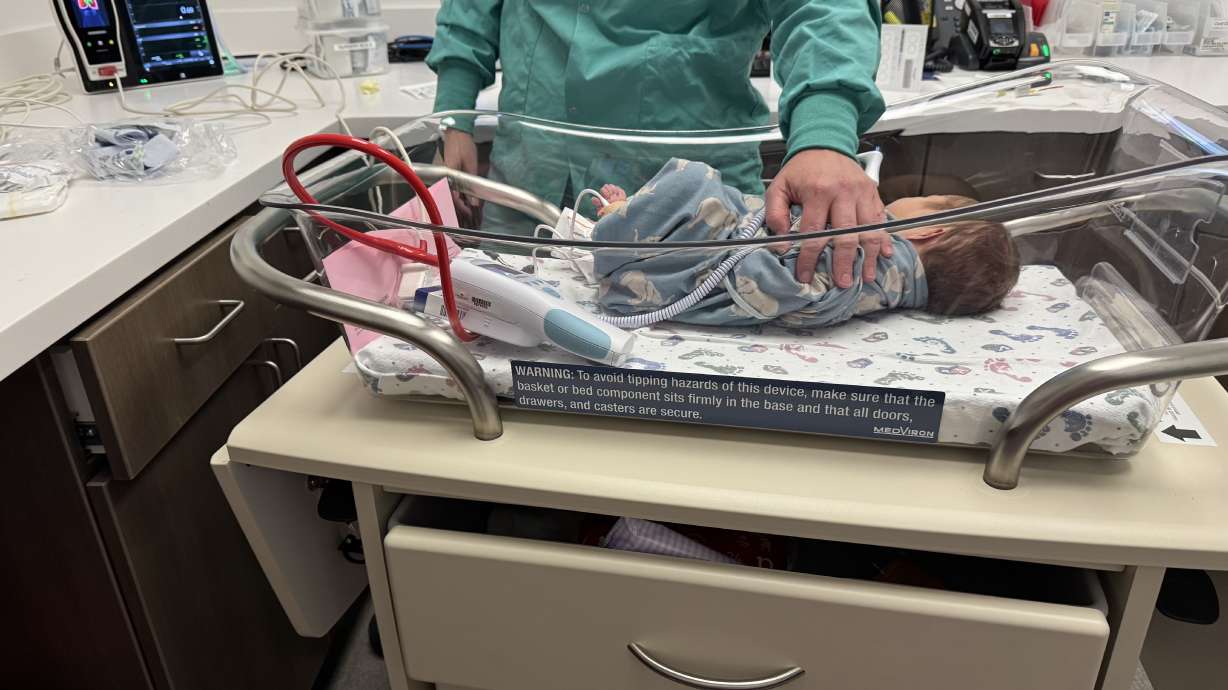

SALT LAKE CITY — New parents may cringe thinking about the heel pricks routinely done after a baby is born and then again two weeks later, but the required screening saves lives.

"I have had cases where I'm calling a parent of a 3-day-old baby, saying, 'You need to go now to the emergency room' ... and they end up getting admitted and cared for based on newborn screening. And it literally saved that child's life," said Mary Rindler, newborn screening program manager with the Utah Department of Health and Human Services.

The addition of a new condition to Utah's list of conditions screened for on Tuesday will help a few more parents and infants receive a diagnosis sooner and access needed specialized care.

That condition, Hunter syndrome or MPS-II, is a rare disorder that causes developmental delays and can lead to irreversible organ damage and early death, but early diagnosis can prevent that. Rindler said treatment is most effective for Hunter syndrome when it begins before symptoms start, which is often around six months.

"Screening is a simple act that has significant, long-term impacts on the child's overall health," Rindler said.

She tells parents they will forget about the screening, with so much going on, caring for a newborn, but those who need to be reminded of it to get their infant specialized care will be contacted. The health department's program also connects them with resources.

Rindler said that although Hunter syndrome is quite rare, they expect to find just one case every one or two years. When you look at all the disorders for which they test, now 45 of them, finding a rare disease turns out to be relatively common.

She said that one in 300 newborns is expected to have one of the conditions identified in newborn screening. Congenital hypothyroidism is one of the most common things found in Utah's screenings, along with cystic fibrosis and phenylketonuria or PKU — the disease the test was designed for and named after.

Rindler said that for each condition they test, early detection is important and can lead to treatment that limits the impact of ongoing disabilities. For PKU, diet changes can lead to significantly better outcomes.

For some of these conditions, infants may develop symptoms within days; for others, it may take months. This screening helps those infants and parents in both categories avoid a "diagnostic odyssey," as Rindler called it. Instead, they have one test and a referral to a genetics clinic or other resources to help get them care.

"We're here to help, and we're here to make sure all babies in Utah are cared for. And that's not just a snippet ... that's our goal," she said.

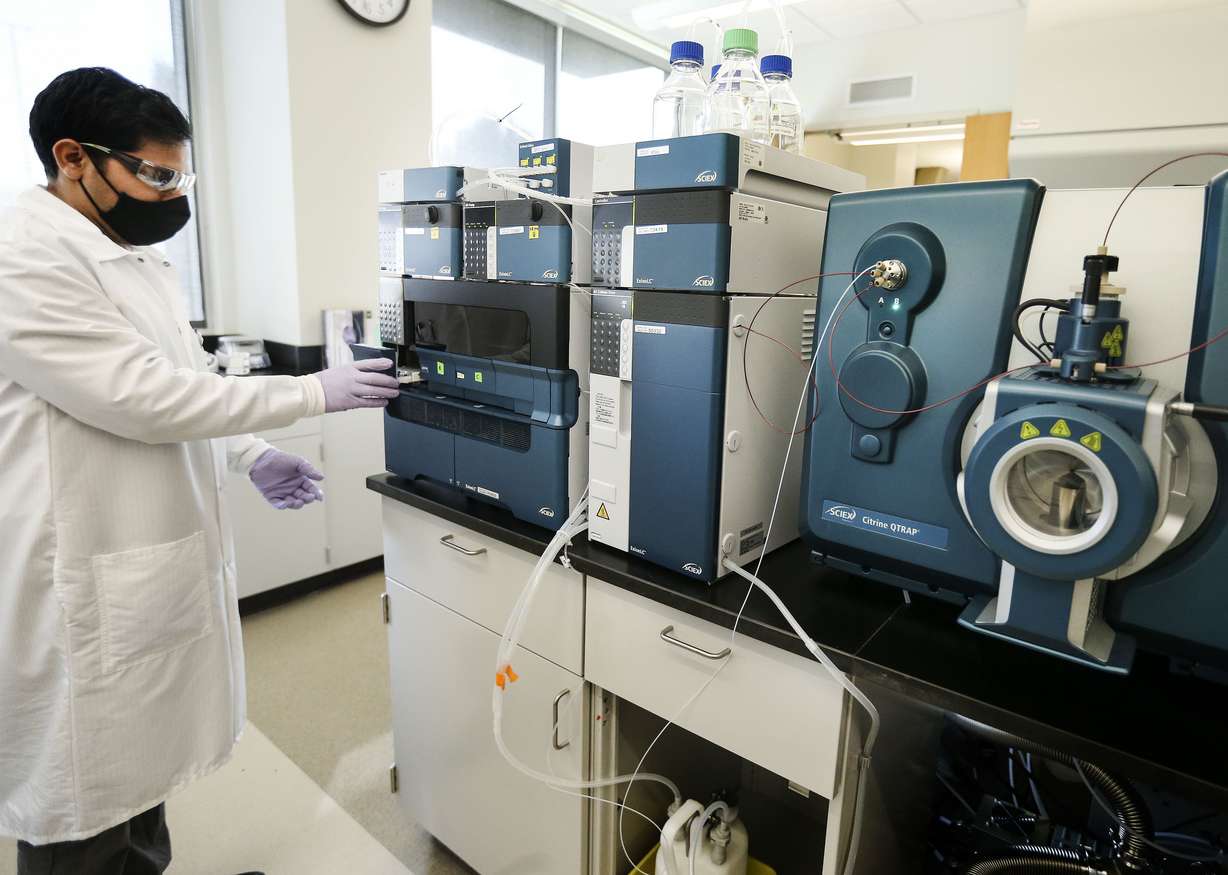

Rindler said organizing the addition of Hunter syndrome and beginning testing is "quite a feat." She said there are a lot of things to consider — including whether the state can test for a new condition and whether it should.

She said an advisory committee reviews factors such as cost, feasibility and benefits. It needs to determine whether the condition affects newborns and if it can be treated. They consult with physicians, specialists and parents before a decision is made by the Utah Department of Health and Human Services' executive office.

She said Hunter syndrome had previously been added to the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel, a list of recommended diseases for screening. It currently has two disorders, she said, that were recently added, which Utah is in the process of considering for its screenings.

Rindler said parents are required to have their newborns screened, and the $148 cost of the screening is billed to parents, although it can be covered by insurance. She said, however, that individual tests could cost significantly more.

Each test added, Rindler said, costs only cents. She said the test is not a diagnosis, but a screening that could lead to recommendations for further testing.

"We're able to do this in an efficient way, in a cost-effective way," she said.

Although screening is required for all newborns, with rare exceptions based on religious beliefs, parents have a choice. They can either authorize the health department to retain their samples for the next seven years or request that they be destroyed immediately.

Rindler said they just inform parents about the service, but do not encourage either decision. She said the retained data can help them conduct population studies and develop screenings for new diseases on the panel, such as Hunter syndrome.

"We want to be as transparent as possible," she said.

For more information about newborn screening in Utah, visit newbornscreening.utah.gov.