- Partnerships and data highlight key lessons of the Great Salt Lake in the past year.

- The lake remains well below its minimum healthy level.

- A new report outlines shifting water consumption changes in the lake's basin.

Editor's note: This article is published through the Great Salt Lake Collaborative, a solutions journalism initiative that partners news, education and media organizations to help inform people about the plight of the Great Salt Lake.

SALT LAKE CITY — A group of Utah leaders and prominent residents gathered on a deck near the eastern shores of the Great Salt Lake on a hot September afternoon last year to outline a vision they had for the Utah 2034 Winter Olympics and Paralympics.

They had just signed a public-private charter, GSL 2034, which aims to restore the Great Salt Lake to its minimum healthy level in time for the Games. The group intends to raise $200 million for lake restoration efforts, with half pledged by Ducks Unlimited.

"We will not let the Great Salt Lake fail," said Gov. Spencer Cox as he announced the mission in September.

Getting there won't be easy. Utah State University experts estimate it'd take approximately 800,000 additional acre-feet per year to get the lake there in time for the Games, but a large group of Utah researchers says the ambitious goal highlights one of the key lessons of the past year that is needed to solve the lake's woes.

Partnerships and "shared responsibility" are needed to save the Great Salt Lake.

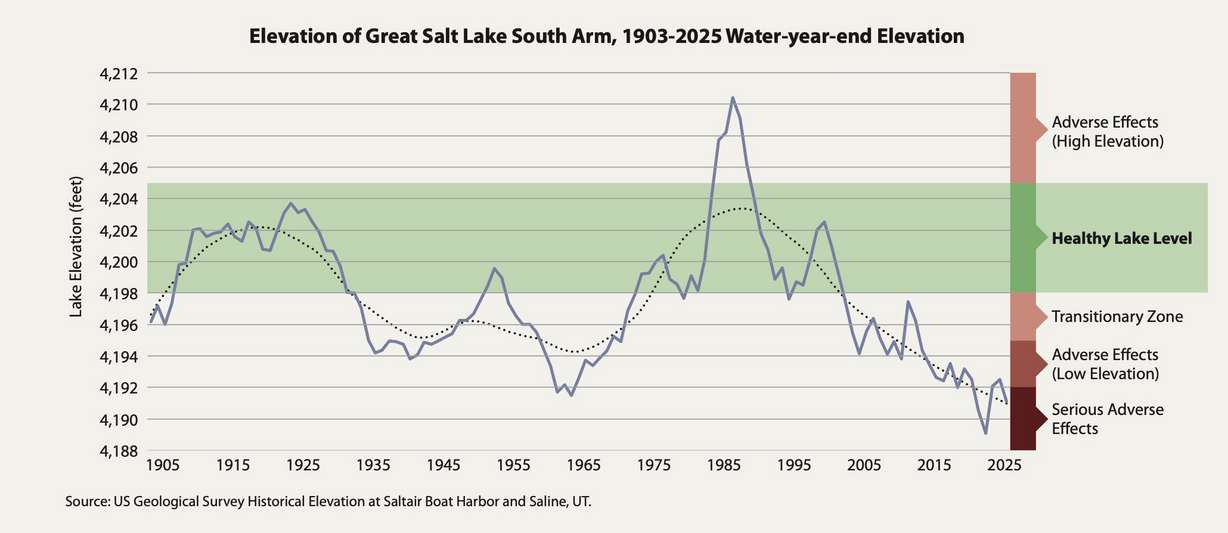

It's one of five key takeaways from another tumultuous year for the lake, which fell back to the "serious adverse effects" range of its health, and ended the water year that month with its third-lowest elevation in over 120 years.

"The good news is we're well above where we were at the start of 2022. The bad news is that we're not that far, where you can have a bad winter, spring and summer and end up in a very tenuous situation," said Brian Steed, the state's Great Salt Lake commissioner, referencing the year the lake reached its all-time low.

What the lake did gain last year was more partnerships, as well as new funding and planning tools that seek to address long-term solutions, the Great Salt Lake Strike Team wrote in its 2026 Great Salt Lake Data report.

The annual report, released Wednesday, compiled the latest data and insights from state universities and agencies. It points out that more collaboration and data are needed in long-term solutions. While the lake has gained some since October, it remains 6½ to 7 feet below what's considered its minimum healthy level at the start of this calendar year.

It also outlines four other key lessons, as well as new data from the past year:

- Utah now has enough information to begin "assessing the effects of policy, conservation programs and management decisions" with the data that has been collected thus far.

- Better data will improve water delivery tactics to the lake.

- Data will also help inform "tradeoffs" within dust, habitat salinity, hydrology and other lake "interactions."

- Utah is shifting from "crisis response" to "long-term stewardship" of the lake.

Where is the water going?

Previous reports outlined how upstream diversions and evaporative loss are behind the lake's historic decline, but this year's report shows how consumption trends are changing. They also better highlight the "shared responsibility" in getting water to the lake.

Total water depletions from the first four years of this decade are up 5% from the first four years of the 1990s, but agricultural use is starting to slide as other uses have risen. Agricultural use still accounts for the most use, but it's dropped from 71% at the start of the 1990s to 65% in the first half of this decade.

Municipal and industrial use — the second-biggest consumer — rose from 24% to 27% in that same time.

Some of that comes from the state's residential growth over that time. Outdoor watering accounted for 97% of all municipal and industrial water consumption in 2024, according to the report. Approximately 408,500 acre-feet of water was used on residential lawns, which was about a quarter of all agricultural consumption.

This has taken a toll on the Jordan River the most among the lake's tributaries, accounting for the vast majority of its depletion. This shows that improvements must be made within this sector, said Utah House Majority Leader Casey Snider, R-Paradise.

"It's really an 'us problem' now, and so we have to figure out how, collectively, we're going to fix this issue at an individual level," he said, during a panel discussion about the report that the University of Utah Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute held Wednesday.

Mineral extraction use remains about double from three decades ago. It accounts for about 6% of water use, which is the third most water-depleting source, but the number is down significantly after peaking in the 2010s. Some of that is tied to newer legislation outlining how mineral companies use water, while U.S. Magnesium's recent shutdown may continue this trend, too.

Previous reports outlined how upstream diversions and evaporative loss are behind the lake's historic decline, but this year's report shows how consumption trends are changing. They also better highlight the "shared responsibility" in getting water to the lake.

New stream gages, diversion measurement tools, groundwater research and mineral industry reporting may help identify future conservation yields with the best benefits in future reports.

What's next for the lake?

Another report is expected to be released later this month that outlines potential costs and options to mitigate dust from the dried lake, which is one of the bigger question marks as the lake remains near its record low. It will offer a dozen ideas to address the issue, such as using water to target dust "hot spots" or finding ways to strengthen the lakebed to reduce dust, said Kevin Perry, a professor of atmospheric studies at the University of Utah.

Better dust data, he adds, will be available in the coming years, as the state builds up a network of dust monitoring sites.

"We all hope that the dust network will show that dust events are not frequent and not severe enough to cause health impacts, but the state needs to be proactive and plan for what needs to be done if that's not in fact the case," he said.

That and the annual strike team report will be available for lawmakers as they make decisions during the legislative session, beginning on Jan. 20.

This year figures to literally be a "watershed year" in lake policy, said Joel Ferry, director of the Utah Department of Natural Resources. The state plans to launch an improved water leasing program, while "big money" is directed at lake solutions. These mechanisms will help the state pump more water into the lake.

"It's going to help us as we deliver these hundreds of thousands of acre-feet needed for the Great Salt Lake," he said.

Will it be enough to help Utah reach its lake goal for 2034? Only time will tell, but everything gathered thus far indicates that the lake can return to 4,198 feet elevation someday, which researchers find promising.

Being able to get the lake to where it's normally at 4,195 feet elevation by then would also be an accomplishment, as it seeks to get the lake to its minimum healthy level beyond the Olympics, Steed adds.

"The state has stepped up to the challenge, and we have put the lake back on a healthier trajectory," he said. "I do believe we can (get) there, and I look forward to that story being told."