Estimated read time: 3-4 minutes

- Utah researchers discovered a new nematode species, Diplolaimelloides woaabi, in the Great Salt Lake.

- Named after the Shoshone word for worm, it's unique to the lake's ecosystem.

- The species may be a leftover of Utah's prehistoric ecosystem or introduced by migrating birds.

Editor's note: This article is published through the Great Salt Lake Collaborative, a solutions journalism initiative that partners news, education and media organizations to help inform people about the plight of the Great Salt Lake.

SALT LAKE CITY — Nematodes were proven to be part of Great Salt Lake's ecosystem through a study published last year, but Utah researchers now say that at least one of the tiny roundworm species found in the lake is different from the hundreds of thousands of other documented species of its kind.

The discovery of Diplolaimelloides woaabi, a previously unknown nematode species, was outlined in a new study published in the Journal of Nematology last month. It follows up on the work of University of Utah assistant professor of biology Michael Werner and other Utah researchers who determined that nematodes live in the lake.

Researchers had a hunch that the Great Salt Lake's nematodes were a new species from the beginning. It just took years to confirm their suspicions. As they further explored the nematodes, they determined that the lake is home to at least two different species, including one with characteristics that hadn't been documented within the over 250,000 known nematode species in the world.

"It's hard to tell distinguishing characteristics, but — genetically — we can see that there are at least two populations out there," Werner said, in a statement on Thursday.

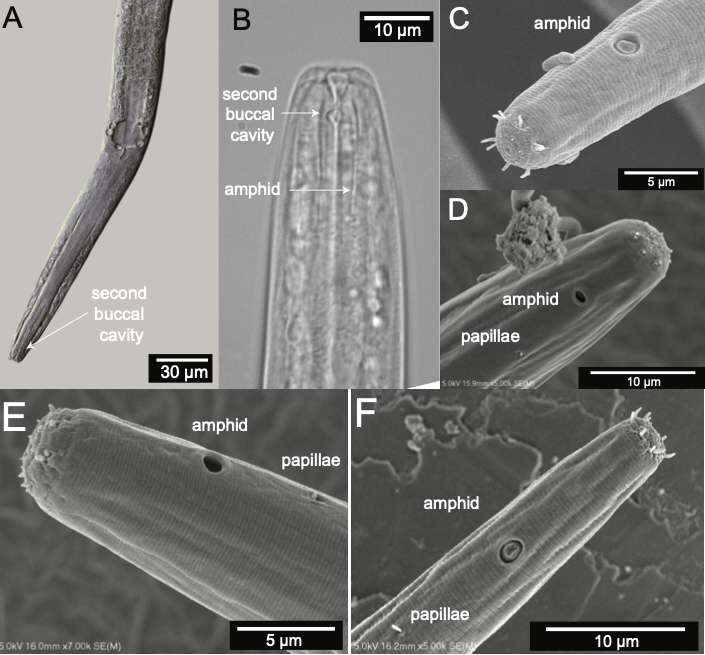

Smaller than 1.5 millimeters, the new species of the two is part of the Diplolaimelloides genus, a pod of species typically found in saltier environments, like coastal marine areas. Its features were unique from those of others in the genus, though, leading to what's now just the second nematode species documented as living outside of an ocean habitat.

Given that the lake rests on the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation's ancestral land, the team brought their findings to the Native American tribe. Leaders chose the name "wo'aabi," or "worm" in the Shoshone language, researchers noted in the paper.

The Great Salt Lake is also home to brine shrimp and brine flies, which were previously believed to be the only species living in the water. What role nematodes have in the lake's ecosystem remains unknown, but researchers wrote that Diplolaimelloides woaabi is "notable for its adaptation to hypersaline microbialites" and is a "potential bioindicator of ecological change in Great Salt Lake."

Its relationship with the rest of the ecosystem could be answered in subsequent studies. The same goes for how a coastal nematode genus ended up in the lake.

Researchers currently have two leading theories.

Diplolaimelloides woaabi could be living relics of Utah's prehistoric past. What is now Utah was once the western shore of a marine waterway that cut through the middle of modern-day North America, said Byron Adams, a Brigham Young University biology professor, who is among the study's 10 authors.

"This area was part of that seaway, and streams and rivers that drained into that beach would be great habitat for these kinds of organisms. With the Colorado plateau lifting up, then you formed a great basin and these animals were trapped here," he explained.

The other theory is that they were introduced to the Great Salt Lake by its most frequent visitors. Diplolaimelloides woaabi may originate in some saline lake in South America and ended up in the Great Salt Lake on the feathers of the millions of birds that frequently migrate between the two hemispheres, either stopping by the lake on their journey or settling down at the lake for the summer.

Werner agrees that this idea sounds a little preposterous, but it's plausible.

"(It's) kind of hard to believe, but it seems like it has to be one of those two," he said.