- Brian Higgins credits bananas for saving his life from PTSD effects.

- Growing up in Belfast, Higgins faced sectarian violence and severe trauma.

- He founded "Mentally Healthy F.I.T." to help others with mental health issues.

SALT LAKE CITY — Brian Higgins says bananas helped save his life. It may sound like a punchline is on its way, but Higgins isn't joking. This is a story about a child caught in the crossfire of sectarian violence and the aftermath of post-traumatic stress disorder that, as an adult, almost destroyed him.

Higgins grew up in Belfast in Northern Ireland during a 30-year conflict known as "The Troubles," fought over the fate of the country. Unionists, mostly Protestants, wanted to remain part of the United Kingdom, and nationalists, mostly Catholic, wanted independence. Shootings and bombings were commonplace.

Higgins' father was a police inspector, and so his family was considered a target by the nationalists.

"I'd been raised to always, you know, (be) hypervigilant, look around, check under the car, you know, be careful who's talking to you, what are their names, all of these elements," he said.

When he was 4, the doorbell rang and he answered the door. A group of men said they wanted to see if his parents wanted their driveway resurfaced.

"I noticed that … the main guy had something … underneath his shirt," he said.

Higgins sent them away and got help. The men were from the Irish Republican Army and, Higgins said, came to try to blow his house up. It was a bulletproof vest that the man was wearing under his shirt.

The impact of bad memories

Higgins, who frequents storytelling forums, related this story at The (now defunct) Bee.

Higgins said he faced violence throughout his formative years. He'd been dragged out of a car and had a gun pressed to his head. He'd had his right leg shattered by a cudgel and, instead of going to a hospital for treatment (because it was a sectarian hospital and, he said, not safe for him), applied a bag of frozen peas to his broken bones.

But Higgins and his family never talked about the emotional impact of the conflict.

"There was no crying involved. There was no asking for help … And it was a very, very masculine, very tough, tough world," he said.

Instead, beginning at age 11, he drank. By 19, he went to his first Alcoholics Anonymous meeting.

Higgins came to the States through the Walsh Visa program, designed to give opportunities to young people affected by "The Troubles." However, he still couldn't escape that violence because it kept replaying in his head.

He said, at times, he was truly convinced that there was a bomb under his bed.

"And in all my Celtic wisdom, I just drank more," he said. "But it didn't make it go away. It just made everything on my way go away. Made all my friends, family, jobs, all out the door."

Higgins said he lived in Boston during this rough time in his life.

"I'd be out in the snow in my boxing shorts, you know, in the middle of the night just totally incoherent. And I'd be in another psych ward and another treatment center, and people did not know what to do," he said.

He said he knew that he was experiencing stress and trauma from memories, but at the same time, he was convinced it was all "happening right now."

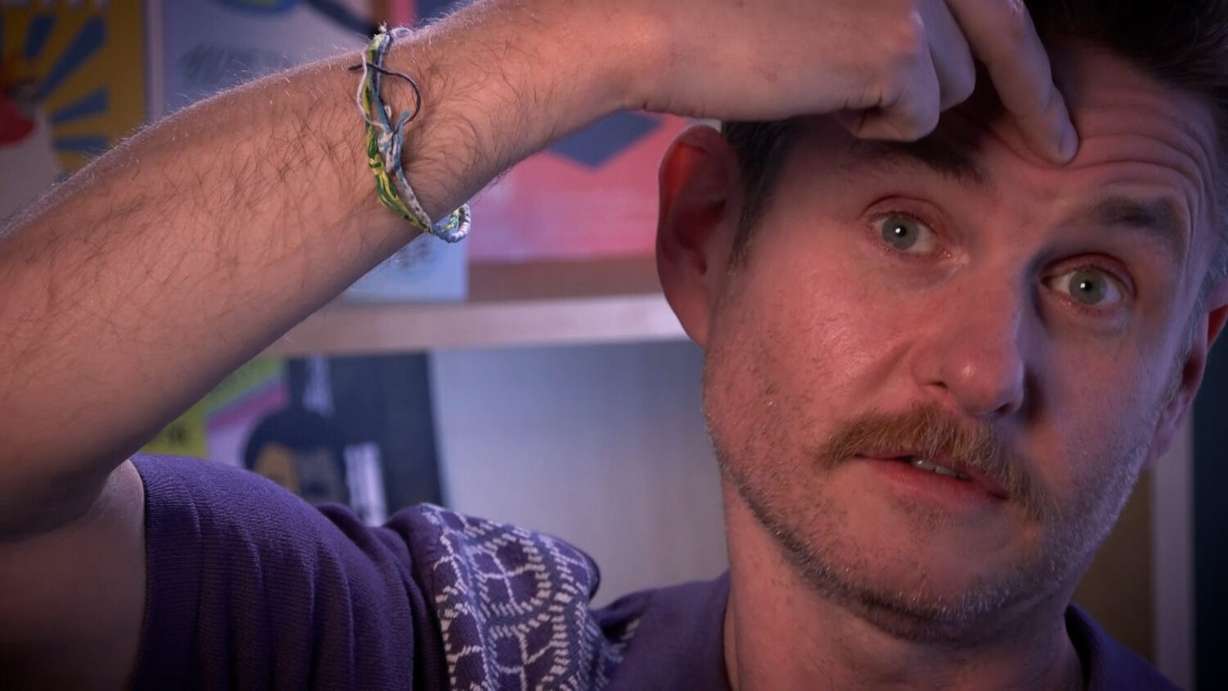

"My main flashback was a gun to my head. At that stage, it was 24 hours a day. Was just right there, right there, right there, right there," he said, miming a gun pressed to his forehead.

How Higgins began helping Utahns

He said he ended up homeless in Salt Lake City and was drinking himself to death.

Until one day, Higgins said, he was in Pioneer Park and two small boys were playing war using bananas as guns. They came over and "shot" him with their bananas.

"The idea popped into my head that if those two kids are truly believing that the bananas are guns, which they are in the child's imagination, there's no reason that I can't believe the opposite is true. That guns are the bananas," he said.

He began drawing his memories with rudimentary stick figures, replacing the guns with bananas.

"I did this every day. I did some kind of creative interpretation of my adverse memories," he said. "It allowed me to reframe (those memories)."

He said he was eventually able to get sober, find sustainable housing and reclaim his life.

"It was keeping me sober, it was helping me," he said.

He thought it could help others.

He started working with veterans on the Veterans Administration Salt Lake campus.

He eventually created a nonprofit called "Mentally Healthy F.I.T." that now works with schools, the Youth Resource Center for homeless youth and substance abuse treatment centers.

"The whole goal is to help people (to) be able to express themselves (about mental health) in a more constructive, communicative manner that the community can understand," he said.

Recently, he arranged a series of portraits of Utahns in their "happy places," or as Higgins calls them, "recharge spaces." Higgins interviewed each person on video and then on stage at a public event, unveiling the portraits, shot mostly by photographer Jesse Justice.

Aitch Alexander, former Navy and NSA data analyst and now writer and performer, who said he's dealt with anxiety and suicidal ideation, spoke onstage about learning to cope with his issues.

"It's not that it gets better, you get stronger so you can deal with it," he said. "You build resilience."

Alexander has a tattoo on his arm that, facing him, reads "stay alive."

"Every day, it feels like I'm on the battle of life and every day is a war and every day I'm coming back from battle and I'm alive," he said.

Higgins said the happy childhood he didn't have early in life, he's having now with his 15-year-old son, Charlie.

They go geocaching, have adventures traveling together (this week in Cambodia) and, since Higgins is a film fan and occasional filmmaker, watch movies together.

"I am having my Steven Spielberg, teenager on a bike, time now with my son, and it's incredible," he said.