Estimated read time: 5-6 minutes

- Research shows U.S. economic mobility has declined since the 1940s.

- Neighborhoods significantly impact children's future economic prospects, data reveals.

- A Harvard economist suggests policy solutions like reducing segregation and increasing education access.

SALT LAKE CITY — Is the American dream on a slow march to the grave?

The adage suggests any child born in the U.S. should have the opportunity, through hard work and determination, to do better than their parents. And once upon a time, it held up pretty well.

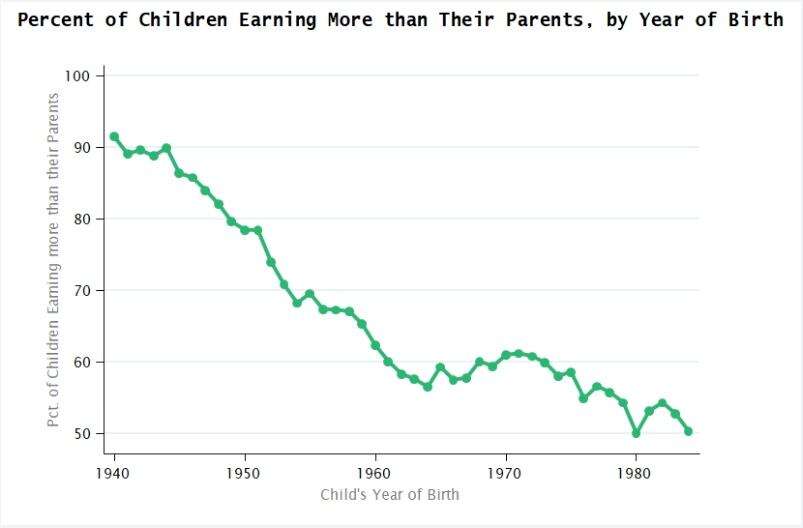

Back in the 1940s, it was almost a guaranteed path for children to surpass the living earned by their parents, with some 92% of those progeny moving up the economic ladder, according to data shared in a presentation by renowned Harvard economist Raj Chetty on March 27 at the University of Utah's Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute.

But by the 1980s, that virtual lock had faded dramatically, Chetty said, and children of that decade were facing even money — 50/50 odds — to surpass their parents on the income metric. And that's about where their chances remain today.

Chetty is the William A. Ackman Professor of Economics at Harvard University and the director of Opportunity Insights, a Harvard-based group of researchers and policy analysts working to address a fundamental challenge: How can we give children from all backgrounds better chances of succeeding?

Utilizing massive amounts of data going back decades, Chetty and his team have identified the underlying factors behind the profound backslide in American economic mobility with the hope that by recognizing causal issues and vetting potential policy solutions, the trend can be reversed.

Where you're from matters

Chetty notes, perhaps not surprisingly, that the location of a child's neighborhood has a major impact on their future economic prospects.

"Where you grew up, the community you were living in, is a critical determinate of your life outcomes," he said.

Chetty said that the data clearly reflects that childhood environment has a direct impact on future economic prospects but has a waning influence the older a child gets. By adulthood, the influence essentially disappears.

Chetty shared a heat map of the U.S. showing the variations, divided by zip code, in levels of economic opportunity across the country. Children who grow up in low economic mobility zones have the lowest chances of bettering their parents' economic prospects while those in high mobility neighborhoods are likely to level up.

The strongest characteristics of high economic mobility areas, according to Chetty, include:

- Lower poverty rate.

- More stable family structures.

- Better K-12 levels schools and easier access to higher education.

- Social capital.

"In the U.S. as a whole, about half of the disconnection we see between low- and high-income people is driven by segregation by income," Chetty said. "We tend to live in different neighborhoods; we tend to go to different schools, different colleges and so on."

The other half of that separation, according to Chetty's research, is driven by friending bias, the tendency for individuals to form friendships and connections with those in their own socioeconomic sphere. One study found that poor children with a friend network of 70% wealthier kids would realize future incomes 20% higher than peers without the cross-class connections.

Bridging class divides is key

Those cross-class relationships, according to the 2022 study, had stronger economic impacts than school quality, family structure, job availability or a community's racial composition.

To grow the pool of American children with elevated economic mobility, Chetty said policy solutions would be most effective in targeting three areas:

- Reducing economic segregation.

- Making place-based investments.

- Increasing access to higher education and workforce training.

Chetty cited a housing subsidy pilot program in Seattle in which half the families received vouchers for housing in whatever area they chose, while the other half received vouchers along with additional social support to secure homes in higher opportunity neighborhoods. In the control group, only 14% of families moved to higher opportunity areas but the rate rose to 54% among families in the supported group.

The rate of the return on investment for those families in high-opportunity areas is on track to be substantial, Chetty said, with children from those families likely to see their lifetime earnings elevated by $200,000.

Another exploration of policy-based solutions, led by Opportunity Insights, is the Collegiate Leaders in Increasing MoBility Initiative, a partnership between leading higher education economists, policymakers and a diverse set of U.S. colleges and universities.

The initiative is seeking to understand not only which colleges act as engines of intergenerational mobility, but why and how schools and policymakers "can promote opportunity and economic growth by helping larger numbers of low-income students reach the middle class."

Utah is an economic mobility leader

Chetty noted that while Utah has earned top billing in the country when it comes to economic mobility measures, at a neighborhood level there remain deep divides across the state for children's relative chances, depending on where they live and the opportunities they can access, to move up the socioeconomic ladder.

A wide swath of current and former Utah policymakers were in attendance for Chetty's presentation last week, including former Utah Sen. Mitt Romney, former Utah Gov. Mike Leavitt, Utah Senate President Stuart Adams, Utah House Speaker Mike Schultz, as well as municipal government representatives from the Salt Lake City Council and other communities.

In comments made following Chetty's presentation, Schultz noted his personal journey as an individual who has ascended from his childhood economic position.

"We are these numbers," Schultz said, referencing the data from Chetty's presentation. "Most of us started out at a different economic scale than we're currently at today. Personally, I was on the bottom end of the middle income class. I grew up in a community where I was fortunate enough to have great mentors … and (connections with) people on the upper end of the income scale."