Estimated read time: 3-4 minutes

- Westminster University researchers plan to study brine flies in the Great Salt Lake.

- The university received a $50,000 Northrop Grumman grant.

- Research aims to inform future management plans, crucial for millions of migratory birds.

Editor's note: This article is published through the Great Salt Lake Collaborative, a solutions journalism initiative that partners news, education and media organizations to help inform people about the plight of the Great Salt Lake.

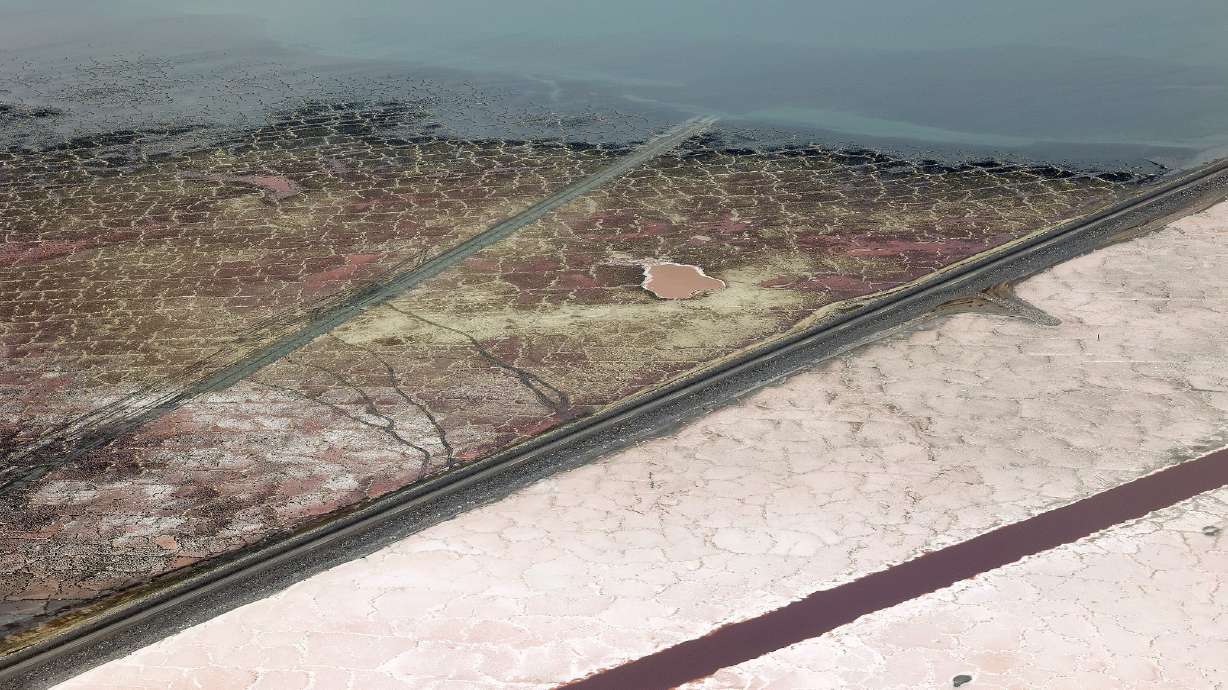

SALT LAKE CITY — When the Great Salt Lake reached an all-time low three years ago, it generated a new concern about one of the few species that live in the lake.

Biologists arriving at the lake to count shorebirds in August 2022 weren't just stunned by the lake's low levels, but they were also surprised to not find many brine flies, a vital food source for the millions of migratory birds that rely on the lake every year.

"Even anecdotally, people were like, 'Gosh, it seems like there's a lot less bugs,'" Janice Gardner, an ecologist for the conservation nonprofit Sageland Collaborative, recalled in 2023.

Georgie Corkery didn't see it firsthand as a researcher at the time, but she's heard all the stories about how "lifeless" the lake was. She's now leading a study to explore how water salinity and other variables, like temperature and seasons, affect brine fly populations at the lake.

Corkery, coordinator of the Great Salt Lake Institute at Westminster University, and her team received a $50,000 grant from Northrop Grumman, which will help researchers monitor brine flies over the next year. She said her goal is to study brine fly populations over "a few seasons" to see what happens, as salinity levels and other variables often change depending on the season.

She knows that most people likely don't care about brine flies, but they are a vital part of the lake's ecosystem that she believes are worth studying.

"The birds care. There's 7 million to 10 million migratory birds that visit Great Salt Lake annually. ... That's a lot of birds," she said. "They depend on brine flies and brine shrimp. Some of them eat both, and some of them only eat brine flies. And the ones that only eat brine flies, they were out of luck."

Researchers know, from previous studies at other saline lakes, that increased salinity could impact brine fly body mass and overall population. The Great Salt Lake's less-salty southern arm reached salinity levels of about 18% when lake levels dropped three years ago, much higher than its healthy range. Its salinity dropped down again after improved snowmelt and various tactics in 2023 aimed to improve levels.

For the new study, Westminster researchers plan to use equipment that almost looks like PVC pipe with bricks on it, which aims to offer an artificial habitat similar to the microbialites that brine flies flock to on the lake, Corkery explained. From there, they'll grab the blocks and count the larvae and pupae that latch onto the equipment, and study them to monitor health and population.

The goal is to learn more about the relationship between salinity and other variables that can be used in the state's future lake management plans. She points out the state already plans for water levels needed for duck hunting. Future knowledge could lead to similar tactics for brine flies, which waterfowl rely on.

"There are people on the ground — say the (Utah Department of Natural Resources) — who are controlling where water is flowing, at what time and how much so that in certain bays, water is a certain depth or not," she said. "It's incredibly unique and cool that we have this (ecosystem). It is a really vital resource for so many reasons."