Estimated read time: 5-6 minutes

- Utah faces ongoing drought and "abnormally dry" conditions despite recent snowfall.

- Southwest Utah remains severely affected, with snowpack levels below 50% of median averages on top of drought.

- Hydrologists warn there could be reduced runoff efficiency this spring.

SALT LAKE CITY — Another storm passed through northern and central Utah this weekend, dumping as much as 21 inches of new snow in Alta by Sunday afternoon.

However, it skipped southern parts of the state yet again, following a trend that has played out over the past few weeks. Storms so far this winter have generally benefited northern and central Utah but have barely touched southern parts of the state.

It's why Utah's statewide snowpack — now up to 101% of the median average for this point in the season after this weekend — isn't a fair assessment of the state's water levels right now.

The statewide average on Monday is buoyed by averages at or above 110% of the early January median average in the Wasatch Mountains and other parts of Utah's northern half. Many of the state's central mountains are also near 100%, but some southern Utah basins have fallen well below 50% for this point in the year — including parts of the state that remain in severe drought.

About one-fifth of Utah remains in at least moderate drought to start 2025, and most of the state is still considered "abnormally dry." Federal hydrologists say this could impact the spring snowpack runoff even in areas with recent rainfall.

"What that means is we're going to have less optimal runoff efficiency when we get water from all that snow," Jordan Clayton, a hydrologist for the Natural Resources Conservation Service, told KSL.com.

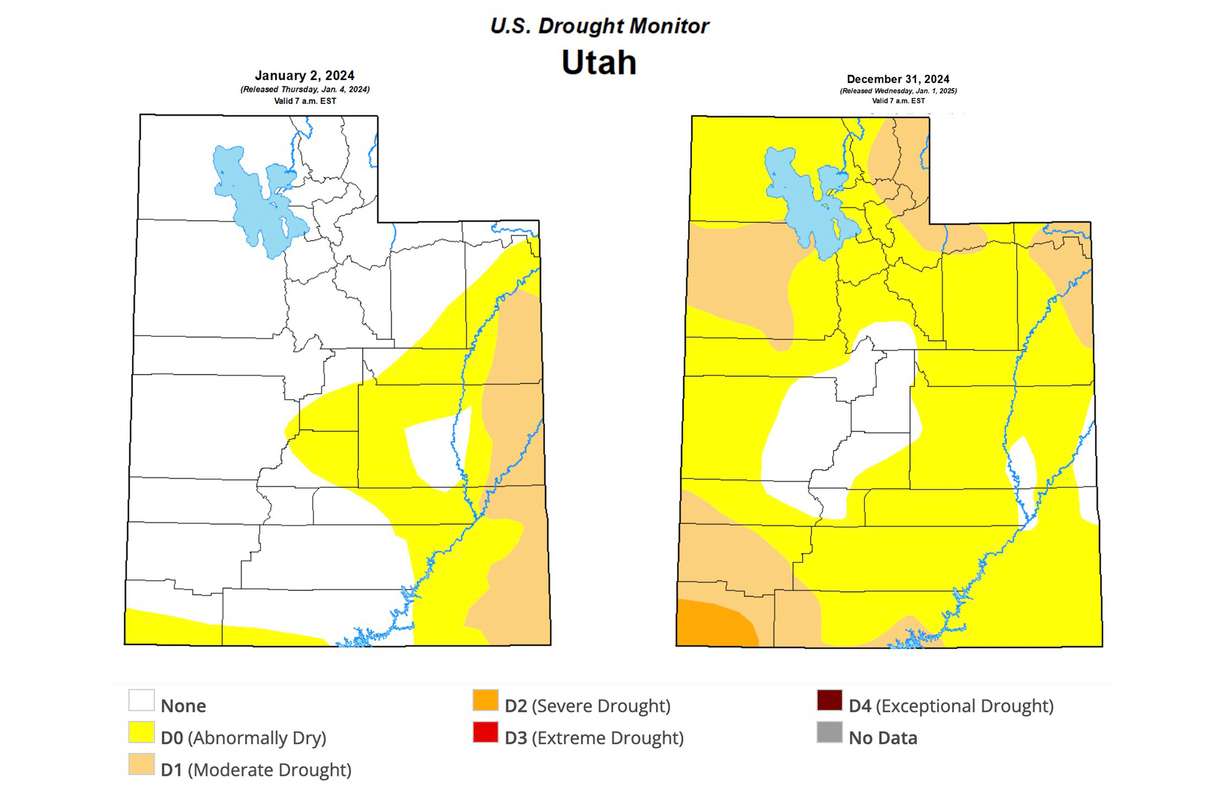

Drought conditions at the start of 2025

There's an adage in Utah climatology that if the state isn't in drought, it's just preparing for the next one. That played out last year as dry conditions emerged mostly after the state collected its second consecutive above-normal snowpack.

There was a brief moment when Utah escaped drought for the first time in five years, but it quickly returned amid weak summer monsoons and fall storms mixed with above-normal temperatures. Utah's southwest, northwest and northeast were impacted the hardest.

About one-third of the state was considered "abnormally dry," and about 10% of the state — all within southeast Utah — was in moderate drought at the start of 2024, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. Now only 12% is not considered in drought or dry at the start of 2025.

Utah's largest drought section covers southwest Utah, where more than half of Washington County is listed in severe drought to start the new year. Extreme drought has also formed in many parts of southern Nevada, western Arizona and southeastern California nearby.

Pockets of moderate drought also remain in the West Desert and a sizeable portion of northeast Utah, which are the southwest end of larger drought conditions impacting Idaho, Montana and Wyoming. Aside from a chunk of central Utah and parts of southeast Utah, most of the state is considered "abnormally dry" compared to what soil moisture levels should be in the state at the start of 2025.

Why it matters

The snowpack collection and spring runoff cycle is important because it accounts for about 95% of the state's water supply — and soil moisture factors into this equation.

Hydrologists learned, especially during the last statewide drought, that water from snow will go into the ground to recharge the groundwater supply before the ground becomes saturated enough to allow for runoff to go into above-ground sources, like streams, creeks and rivers that flow into lakes and reservoirs.

"The less soil moisture you have, the more net loss you're going to have," Glen Merrill, a National Weather Service hydrologist, explained.

Southwest Utah could face a possible double whammy. It's dealing with both below-normal soil moisture and snowpack. The southwestern and Escalante-Paria basins entered this week at 30% and 43% of their respective early January median averages.

Clayton said he's weary of predicting what could happen this spring, but the situation so far puts the region in "rough shape."

"Things are still manageable, but we need to get some snow down in southwestern Utah pretty quickly," he said.

However, even parts of northern Utah that have enjoyed snowfall may deal with issues tied to dry conditions before all the storms. This includes the Great Salt Lake Basin, which has suddenly jumped from 69% of its median average on Dec. 23 to 113% two weeks later.

Soil moisture levels, Clayton explains, don't change much once the snowpack has formed. It essentially locks conditions in place until the snow melts in the spring. So it's possible that the pre-snowpack dryness will impact runoff efficiency there and in other places with drier soil moisture levels before the snow.

"Some of that water that would have otherwise made it downstream will just wind up getting soaked up by the headwater soils," he said.

Given the dry conditions, Utah might need an above-normal snowpack just to get another normal runoff. The good news is Utah's reservoir system is already back to 79% capacity, much higher than it normally is in January, so less water is needed to refill most of them.

The bad news is it may mean drought conditions can worsen this year, especially in areas that haven't received moisture, and less runoff for larger bodies of water like Lake Powell and Great Salt Lake that remain below desired levels.

Looking forward

Long-range forecasts indicate storm activity could slow down across the West in mid-January, but northern Utah has stronger precipitation probabilities, and southern Utah has weaker ones when it comes to the second half of the regular snowpack season.

Hydrologists hope for a strong second half full of consistent activity and atmospheric rivers because, even with all the recent snow, Utah's statewide total right now is only 38% of the median average for the whole year.

"It's still very, very early," Merrill said. "We've got the bulk of our winter season and wet spring ahead of us."