Estimated read time: 5-6 minutes

- The Great Salt Lake's levels have fallen to lows akin to 2021, raising some concerns about its current state.

- Record temperatures and drought conditions contributed to the lake's decline this summer.

- Utah officials remain hopeful about the lake's future, implementing water conservation measures and planning for its recovery.

Editor's note: This article is published through the Great Salt Lake Collaborative, a solutions journalism initiative that partners news, education and media organizations to help inform people about the plight of the Great Salt Lake.

SALT LAKE CITY — The Great Salt Lake is beginning to rebound again as it typically does at this point of the year, but levels dropped this year to a familiar point.

Its southern arm has fallen to 4,192.1 feet elevation, a little less than a foot higher than its northern arm at 4,191.5 feet, per U.S. Geological Survey data updated Wednesday. The two sides, split by the causeway running through the lake, have fallen about 1 to 3 feet since its peak in June, placing the lake in a similar position as the beginning of the 2021 water year.

"That's something that we continue to monitor very closely because, as we know, that was really the start of the precipitous decline that led to the lowest (levels) we saw in history in 2022," said Great Salt Lake Commissioner Brian Steed, in an update with reporters on Wednesday.

However, Steed believes steps that Utah has taken since then — including the creation of the Great Salt Lake Commissioner's Office — should help prevent the lake from falling back to its all-time lowest level of 4,188.5 feet elevation, set a little over two years ago.

A summertime drop

Lake levels normally rise every winter and drop every summer because of climate conditions and water usage. This year's declines were a bit harsher than the Great Salt Lake Commissioner's Office had anticipated.

It's likely tied to the conditions that emerged since the lake rose to its highest point in five years, topping out at 4,195.2 feet elevation at its southern end.

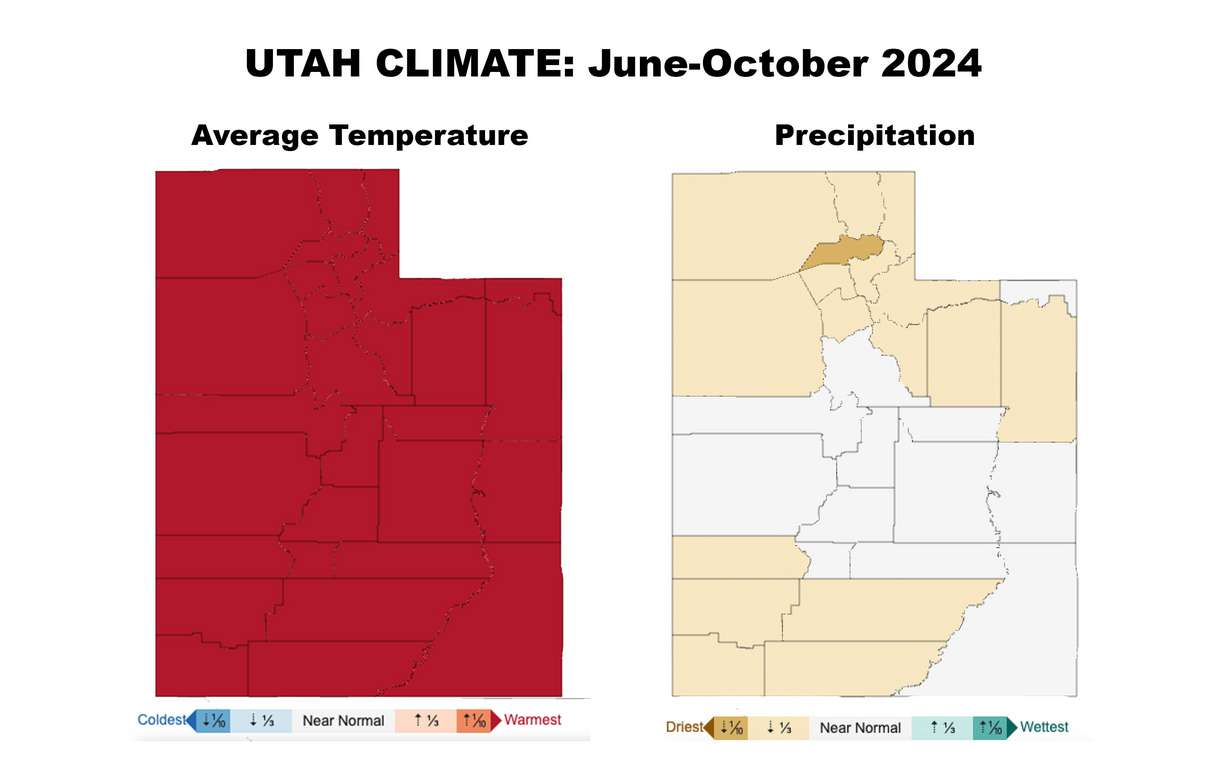

Utah's average temperature between June and October was the highest in the 130 years of statewide record-keeping, 1.3 degrees above any other year since 1895, according to National Centers for Environmental Information data. Its precipitation levels over that time were about an inch off the 20th-century average.

Countywide data shows almost the entire Great Salt Lake Basin and southwest Utah were impacted most by hotter and drier conditions over the past five months. In Weber County's case, the five-month span was the eighth driest among comparable intervals since 1895.

Unsurprisingly, drought conditions have returned to both regions since June. About one-fifth of the state remains in at least moderate drought, including a large chunk of Tooele County and northeast Utah near the lake and some of its tributaries. The rest of the basin is considered "abnormally dry," according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

"We did see more evaporative loss off the lake during that time frame — higher than what we'd hope to see," Steed said.

In the end, the lake's southern arm lost all its gains from the past year while its northern arm is about 2 feet above where it was in mid-November 2023. That's because the state decided to keep a breach in the causeway that was closed most of last year, which may have also factored in the numbers.

Great Salt Lake deputy commissioner Tim Davis said he's aware that the current levels will probably surprise many people, but he believes it goes to show the challenge Utah is up against as it tries to get lake levels back to a range considered healthy for its ecosystem.

"I think a lot of people would — right now, after these last two water years — think that we'd be at a significantly higher level than we're at," he said. "It just shows that we need to continue to conserve, dedicate and deliver water to the lake."

Preventing a repeat

Yet, Steed sees a silver lining in the data.

Given the conditions, he would have suspected the lake would be lower than what it is now. It seems to point to signs that water users are still cutting back consumption when compared to historical trends, which could also explain why Utah's reservoir system remains about 74% full — about the same as this time last year.

"If you look at the municipal and industrial uses, it's probably a little bit down, but agriculture is pretty stable. In both of those senses, it's not been because of increased use; it's been because it's been hot and dry," he said.

Related:

He's hopeful that better conditions will return and enhance the steps taken to get water to the Great Salt Lake since its 2022 low point.

The commissioner's office reported Tuesday that 69,342 acre-feet of water was dedicated to the lake this year — enough water to nearly fill out Scofield Reservoir. About 80% of that comes through permanent or multi-year donations, meaning the lake will continue to receive new water.

Another 700,000 acre-feet of water was directed from releases at reservoirs within the basin, Davis said. The state also reached a landmark deal with Compass Minerals over water usage in September, which the department estimates could save as much as 156,000 acre-feet a year in the best-case scenario.

On top of that, the state is set to release a new 10-year plan for the lake's recovery next month and has implemented a new rule to reclose the breach if southern arm levels drop another 2 feet, so the vital end can refill faster. Steed and Davis say these are some of the ways they believe the lake will avoid a 2022 repeat.

However, they know the lake's future also depends on something outside of their control.

"If we can have really, really wet conditions from here until May — that would be my Christmas present," Steed said.