Estimated read time: 8-9 minutes

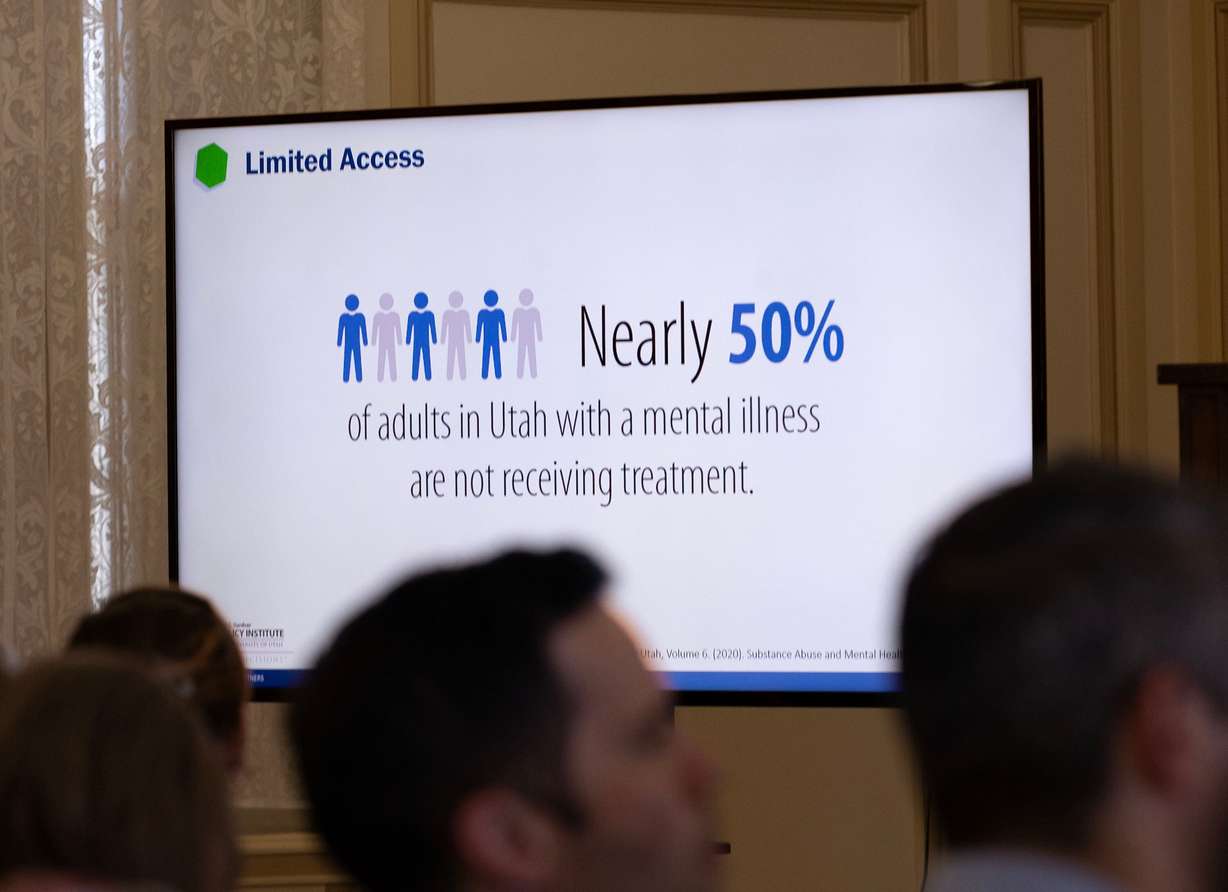

- Utah faces significant behavioral health challenges, with high mental illness rates and service gaps.

- Experts highlight issues like fragmented care, rural access and insufficient mental health resources.

- Stakeholders call for patient-centered solutions and better integration of physical and behavioral health.

SALT LAKE CITY — Utah has a behavioral health master plan designed to make sure the mental health needs of young and old, urban and rural are all well served. It's a daunting challenge.

The Beehive State ranks 11th-highest in terms of adults with any mental illness, third in terms of adults with serious mental illness and fourth-highest for adults with serious suicidal ideation.

The portion of young adults with poor mental health has more than doubled in the past decade, while more than 60% of kids ages 6 to 11 and half of those ages 12 to 16 who have a mental or behavioral health condition don't receive any treatment. Additionally, half of parents whose children need treatment say they can't access it or it's hard for the family to navigate.

Those aren't the only populations in Utah with mental health challenges, a group that includes mothers of very young children and older adults.

The statistics come from the Utah Behavioral Health Master Plan, which was the topic of a Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute breakfast discussion Thursday in downtown Salt Lake City at the Thomas S. Monson Center. A panel that included some of the experts involved with the plan's development and mental health issues in general talked about gaps, needs and what it would take to make Utah a model of mental and behavioral health services.

The state's challenges cover a lot of ground: access to care, an inadequate number of beds available for those in acute crisis, transportation in rural areas where someone might end up in handcuffs to be driven by a sheriff for an issue that is not criminal, fragmentation in a system with a wide range of players and policy and funding gaps, among others.

Meeting the needs is important, as Francis Gibson, CEO and president of the Utah Hospital Association said, because "mental health is health."

Making a plan

A coalition of Utah stakeholders, including the Utah Hospital Association, the Utah Department of Health and Human Services and the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute, at the behest of what was then the Utah Behavioral Health Coalition took on the task of assessing the state's mental health environment, needs, services and gaps around 2022.

The goal, according to Laura Summers, director of industry research at the Gardner Institute, was to see within the behavioral health system "where things were connecting, where they were not and what were the perceptions of where there were areas for improvement." They found mental/behavioral health needs across age groups, with issues like fragmented care and worker shortages, not to mention never enough money.

The master plan is a "living" document and the Utah Behavioral Health Commission is now the central authority for coordinating initiatives between state and local governments, health systems and others, Summers said.

Filling in the gaps

Kyle Snow, vice chair of the commission and executive director of Northeastern Counseling, hails from Roosevelt and knows about the challenges faced in rural Utah, including sometimes just having a seat at the table. He disagrees with the notion that care in rural Utah is more fragmented, he said, because rural areas can engage all the stakeholders there more easily. But he also noted behavioral health issues should not be rural vs. urban.

"There is truly a benefit to the rural areas by building up the urban areas," Snow said. "As those resources become more abundant, then those resources are freed up for us in the rural areas, too."

Transportation is particularly vexing in rural Utah, which will likely never have an acute care hospital for mental health. Right now, when someone has an acute mental health crisis and needs a higher level of care, that handcuffed ride in a law enforcement vehicle may be the only solution. "We can't criminalize behavioral health," he said, noting the officers aren't being disrespectful or mean, but are simply trying to protect those in crisis. "But there's got to be a better way," he added.

There's also a great need for behavioral health staff in rural areas, per Snow.

Angela Kimball, chief advocacy officer for the national mental health advocacy organization Inseparable, spoke of efforts in other states to improve mental health, including making sure services exist in strong form for children and youths. "That is an area that tends to be underdeveloped," she said, "and yet half of all serious mental health issues arise by age 14, 75% by age 24 and that's exactly the age range where we have the fewest services available."

Among states tackling the issue is Colorado, where Kimball said treatment providers are paid above their normal rate to serve those children and families. Colorado also developed a state behavioral mental health expert team to do on-site case consultation when a child has difficulties that are beyond what a facility can manage. The two factors go together: In exchange for the higher reimbursement rate, she said, if the child meets the criteria for a facility, it cannot just discharge a child for being difficult or hard to treat. Instead, the state provides assistance and they together must figure it out.

Skills training for behavioral health staff is also vital, she said. "They are now essentially growing their own capacity to serve some of the most challenged children out there."

Tracking how long people who are having a mental health emergency wait in an emergency department for an appropriate bed and treatment has been a big challenge, said Jordan Sorenson, director of behavioral health and emergency preparedness for the Utah Hospital Association. That holding pattern "is incredibly inefficient, but there's nowhere to send them."

Sorenson also cited a serious need for staff to follow up and make sure patients who are discharged to the community get treatment, peer support and other care they need at a less acute level.

Opportunities for better care

Tracy Gruber, executive director of the Utah Department of Health and Human Services, acknowledges lots of gaps. But she sees in them great opportunity to provide services and improve mental health through a continuum of care.

Lots of efforts — and entities — have a piece of the responsibility for mental/behavioral health, she said, including Workforce Services, her department, law enforcement, the education system and others. "One of the things that was so rightly pointed out is who's the primary organizer of all this. Because we all have the best intentions and if we aren't all focusing on a single outcome and growing in the same direction, to that end, given the lack of resources, we're all going to be kind of scattered in doing our own thing."

The complications are not unique to behavioral health, per Gruber. The solution, she said, is to be "patient-centered."

Kimball said Utah is already a national leader in crisis services, the originator of 988 "and the reason the entire country has that as a three-digital code to dial in a mental health emergency." The state also has impact teams and crisis stabilization facilities. What's not necessarily stable is the funding.

"One of the things I would love to see is actually a sustainable all-care model that makes sure that a diversified set of funding sources are all contributing to make sure" services are available 24/7, she said.

Wish lists

The discussion closed with moderator Ally Isom, chair of the commission, asking for a single high-impact item each person would like to see in Utah.

Sorenson hailed the work the Utah State Hospital does with very limited resources and said the Legislature passed on the opportunity to provide 40 more beds for the sub-acute population that was stable but not able to just go home. They require fewer services, presumably at lower cost, and that would free up acute care beds, he said. Often, there's no bed for the sickest of the sick.

He also hailed an under-used "call up" program available any time where a primary care provider or emergency department doctor can consult with a psychiatrist on a patient's care. Primary care and emergency room doctors are on the front lines and provide most of the care for those with mental health challenges, he said.

Gruber would like to see a centralized entity handle behavioral health efforts statewide, with a focus on being patient-centered. "It's a bureaucratic solution, but ultimately I believe it will lead to better patient outcomes."

She also wants better integration of physical and behavioral health, starting at the primary care level.

Snow, like Sorenson, believes bolstering the state hospital is key. People in acute crisis should be out of the emergency department and where they can get the help they need a lot faster.

The bottom line, per Snow, is to see that complications are set aside where the patients don't have to worry about them and they can access the care they need and navigate the mental health system well.

No state actually has a patient-driven system of care, Kimball told the group, though it gets talked about a lot.

"I think there's a real opportunity here for Utah to take a step back and really think about how do we design our system to really, truly be patient-centered," she said.

It shouldn't matter who the payer is; everyone should have access to a core set of quality behavioral health services, according to Kimball. They should have continuity of care so they can recover, which means care coordination and case management throughout. And systems need to coordinate, too.

Finally, "services should come to where people are," whether they're in jail, on the streets, in schools or at home, per Kimball.

Gruber noted that Utah does have mobile response teams, though on a smaller scale.