Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

- Fourteen states have paid family and medical leave programs, with varying benefits.

- A federal report highlights paid leave as an anti-poverty tool, benefiting 27% of employees.

- State programs differ in coverage criteria and wage replacement, complicating comparisons.

SALT LAKE CITY — Fourteen states have paid family and medical leave programs that allow both parents to take between six and 12 weeks to be with a new child, according to the tracking done by the Prenatal-to-3-Policy Impact Center at Vanderbilt University.

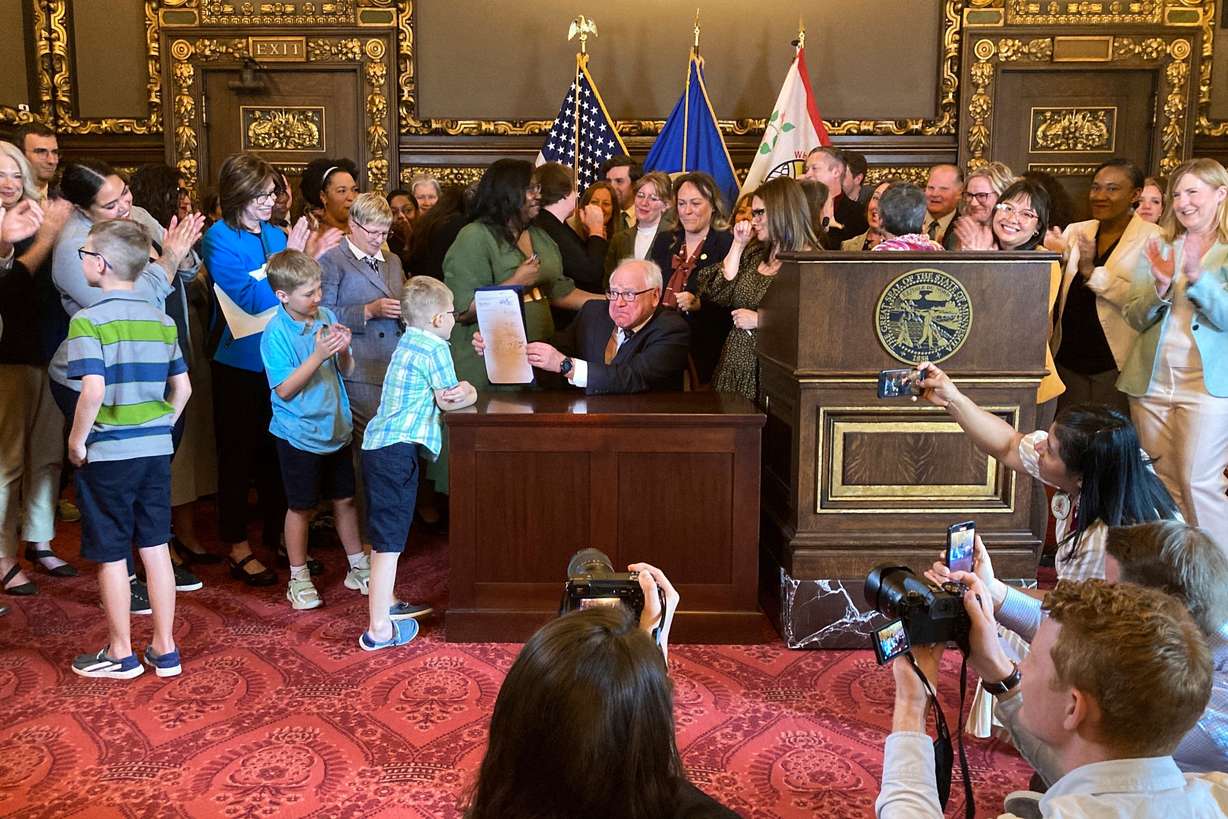

As of Oct. 1, 2024, when the report was published, 10 of the states had implemented programs, including California, New Jersey, Rhode Island, New York, District of Columbia, Washington state, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Oregon and Colorado. The other four — Delaware, Minnesota, Maine and Maryland — are expected to have theirs fully implemented by late 2026.

According to the report, "State paid and medical leave policies allow workers to take time off work and receive a portion of their income for qualifying reasons, which include the birth, adoption or fostering of a child, caring for a loved one with a serious medical condition or recovering from one's own serious medical condition."

Federal report touts benefits of paid leave

In November, the U.S. Department of Labor released a report it commissioned that looked at the evidence that paid leave is an anti-poverty tool. The Urban Institute did the research for the report, which was written for the Labor Department's Women's Bureau.

Per the findings, just over a quarter (27%) of American civilian employees have access to the benefit through their employers. Slightly more than 4 in 10 have access to short-term disability through their employer. Among low-wage workers, just 6% can access paid leave through their jobs.

The institute reported that a national paid family and medical leave law would bump that number to 97% of workers. According to projections, that would reduce poverty by 16% in the families receiving the benefits.

Broad differences in state leave programs

There's a lot of difference in the programs, from how rich the benefits are to who pays and how long someone can have the benefit. "Understanding Equity in Paid Family and Medical Leave Programs" by the Urban Institute, outlines some of the requirements, which vary greatly. "In state programs, worker coverage may be based on a mix of factors, including length of tenure with a current employer, hours worked, earnings during a specified base period or employment location."

That study notes some states use both employment- and wage-based rules. It says that workers in New Jersey, for example, are required to work at least 20 weeks in which they earned at least $260 a week to qualify. Most states rely on a "measure of workers' wages to determine coverage." Meanwhile, in New York, workers have to have "26 weeks of consecutive full-time employment or 175 part-time working days with a single employer to qualify." Workers in Washington state must have worked 820 hours for an employer.

"These differences make it difficult to compare state worker coverage criteria," the report adds.

States have also set different levels of wage replacement. "Benefits range from 60% of wages in Rhode Island to 100% for lower-wage workers in Oregon," per the report, which notes most states have put on cap on benefits.

Eleven of the states allow 12 weeks of paid family leave for full-time workers. Rhode Island passed a law allowing six weeks but followed with legislation that will increase the time to seven weeks in 2025 and eight weeks in 2026. California settled on eight weeks. Massachusetts settled on 11 weeks.

Maryland had planned to implement the program earlier but instead delayed the start of paid family and medical leave to July 2026, per the report.

This year, Colorado changed its law to allow an additional four weeks of prenatal or postnatal leave for the parent who gives birth, in addition to the 12 weeks.

In all the states but Delaware and Washington, as well as the District of Columbia, for instance, a birthing parent can stack medical and family leave to get extra time. The report projects benefits based on the hypothetical situation where a full-time worker earns the national media wage, which is roughly $61,440 a year, per the center. That calculation shows weekly benefits ranging from $709 in California to $1,016 in Oregon.

The laws have been somewhat fluid, too. California, for example, recently removed a feature that let employers require their workers to use up to two weeks of their vacation time before they could get paid family leave benefits.