Estimated read time: 11-12 minutes

SALT LAKE CITY — As Gabe Madsen lie on the ground, it wasn't immediately clear that his life in sports would change. The moment, though, served as a turning point, where one sport was forgotten and the other fully embraced.

Minutes before he was on the ground, Madsen, who was a freshman pitcher in high school, had been tasked with tossing small rubber balls to teammates in a practice session to help improve on hand-eye coordination with a bat by making contact with a smaller object.

Protecting himself behind a pitching screen, Madsen executed the drill he'd done many times before.

"This dude I'm throwing it to missed, like, so many in a row," Madsen recalled. "And so I step out from the net, and of course he drills that one just right back into my eye. And it was super hard contact, because rubber ball, metal bat."

Madsen immediately fell to the ground. His twin brother, Mason, and the batter came up "kind of laughing a little bit" as they approached him. But as Gabe Madsen opened his eye, it was fully red with blood pooled up in his eye.

"He closed his lid, and it hit and bounced off, and the blood pooled up," his mother, Jennifer Krenzelok, said.

"Parts of my eye moved back and blood came in," Madsen added. "And so my dad rushes me to the eye clinic, like, driving 100 miles per hour on the highway."

The injury had done damage to his eye, though doctors believed Madsen would eventually recover and have full vision again. But it wasn't a guarantee, either, and a long rehab followed.

"We had to keep him in the basement, sitting upright on a couch for almost two weeks in the dark," Krenzelok said. "Like, he couldn't even move."

Madsen said "it was pretty scary," but after two weeks he finally got his full vision back. He had to wear goggles "for a long time," though. It was a serious enough injury that Madsen gave up baseball altogether — and his brother followed suit.

Baseball had always been Gabe Madsen's first love. He dreamed — like many who play the sport — of being a pitcher in Major League Baseball, but dreams change; and an injury of that magnitude certainly was a deciding factor.

"From that point, I never played baseball again," he said. "That's my last year. I'm sticking with basketball."

He and his brother gave up baseball and focused solely on basketball, which had already been largely successful as they started to get collegiate offers. The twins remained inseparable through high school before the two eventually chose different collegiate paths.

And though their paths varied a bit over their college career, the two will finish out their career at the University of Utah. And while an NCAA Tournament berth was always the ultimate goal, their time at Utah is more about ending their collegiate careers together.

"Take all the goals out of it, just to appreciate being able to play this last year together," Gabe Madsen said, speaking about playing again with his twin. "And whenever that last game is, hopefully we can end it together and be able to be like that was our last game together.

"I think that was the one thing that kind of we both looked at and we didn't know it was our last game," he added. "It was kind of like a hard thing to accept closure wise. So just to know that that's our last game together would be pretty cool. It's going to be sad, but it'd be cool."

The game will eventually end for each, but the two are soaking up the time they have together again in the sport that's connected them for all these years.

Life as a twin

Make no confusion, Mason and Gabe Madsen are completely different people — even if the two share nearly identical physical traits.

"Totally different people here," Krenzelok said. "Just because they came in a package, we don't treat them like that. I think they've always had each other's backs but pushed one another."

Krenzelok describes the two as having a "unique relationship," but that it's "just this bond that comes with being a twin that I think only twins can completely understand."

Mason has always been the assertive one — the twin who knows what he wants and goes for it. Gabe has been more reserved and "the observer," Krenzelok said. As Mason went, Gabe followed.

"Gabe would just kind of watch and be like, 'OK, I'll crawl, too.' Or, Mason's walking, Gabe is like, 'Oh, all right, I'm gonna walk, too,'" Krenzelok said. "Mason's always been more vocal. Gabe just sits back and kind of waits to say what he's thinking. And it's just as profound, but in a different manner."

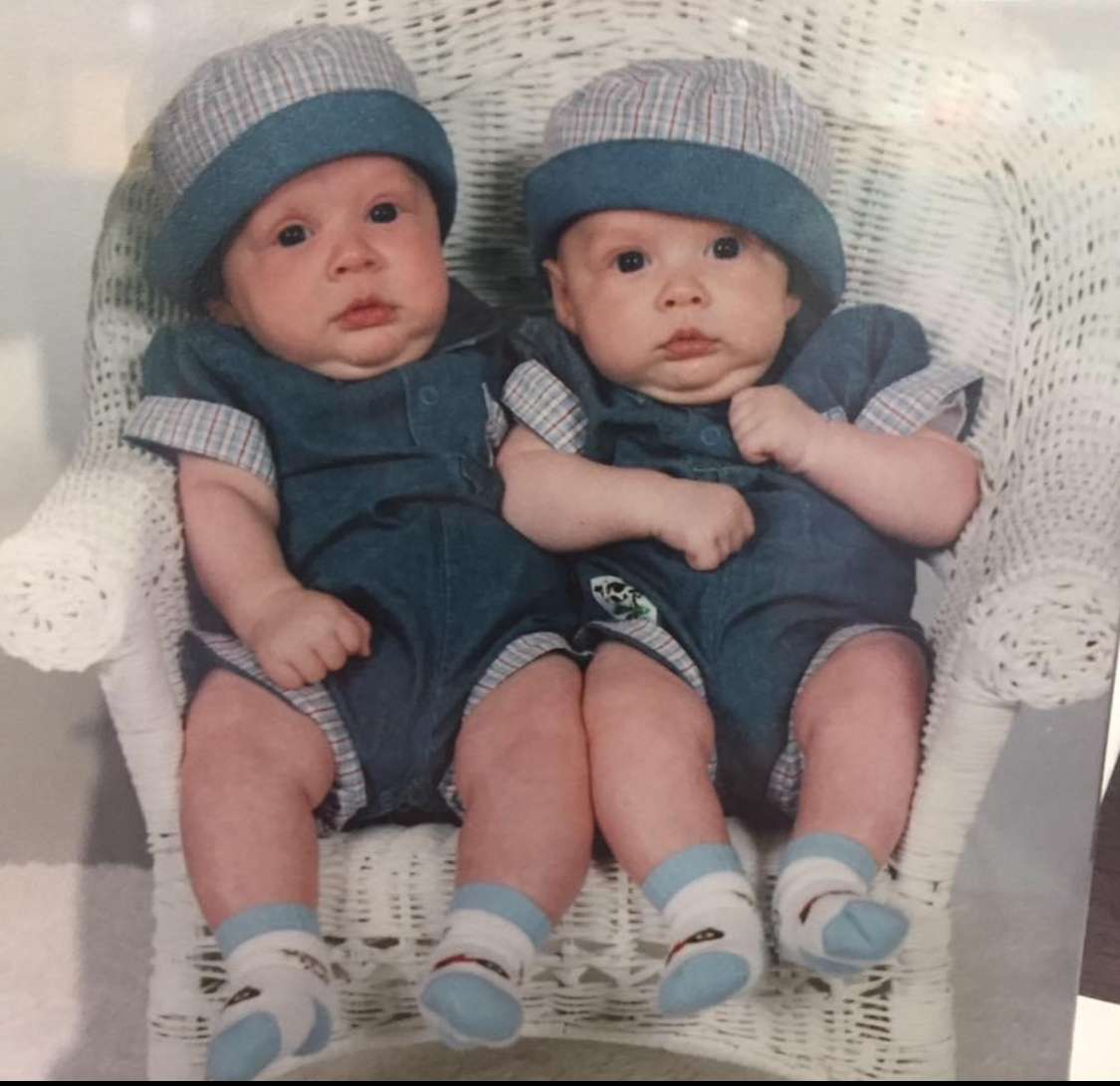

The relationship between the two is most identifiable in a childhood moment that was captured in what is now a cherished photo by the family. Krenzelok happened to capture the moment with perfection with a disposable camera when the two were young.

The photo shows Gabe driving around in a little red and yellow car as a child, with Mason outside of the car, ripping him out.

"He's ripping me out of the car and I'm crying," Gabe says as both he and Mason share laughs as they recall the moment.

But those moments were more rare, the two said. There was always the traditional rivalry that siblings share, but their ability to recover and be best friends again was different.

"This is the thing that people don't understand, even our dad; like our dad was around us all the time and doesn't understand the dynamic of every time we play ones, it almost always ends in a fight," Mason Madsen said. "But we know that we just walk it out and then it's back to normal, kind of. But also, you've got to be careful who sees that, because people can't separate the way we can."

Though the two were nearly inseparable their entire childhood — Gabe recalls only one time being away from Mason, and that was a road trip he took in second grade with a friend for 10 days — Krenzelok wanted the two to have different experiences. As such, they'd have them in different classes in school.

"We've always treated them as individuals, Krenzelok said, "and I think we've really impressed that upon people. ... Having teachers say things where you're trying to compare them, and we're like, 'Nope, totally different people. Totally different people here.'"

"We definitely did everything together," Gabe said. "Like our parents separated us in elementary school, because they wanted us to have different teachers and different friend groups, because we were always together."

But the two always did everything together until the two split ways in their college career.

A life of basketball

Basketball was life for the Madsen twins. And while the two played other sports competitively, it was basketball where the two flourished. It helped that their father, Luke Madsen, was a high school basketball coach.

But there was always an "internal drive" for the two when it came to basketball.

"Even when they were little, it was about playing one-on-one in the driveway, and drawing that 3-point line and then spray painting that on there," Krenzelok said. "I think that they both just have that inner drive."

The family moved from the United States to China to work at a boarding school when the two were in fifth grade. Part of the customs in China included a two-hour break from a school schedule that started at 8 a.m. and ended at 8 p.m.

But for the Madsen twins, they still got the two-hour break, but their school day ended at 4 p.m. With so much down time compared to their peers, Krenzelok said she told them they've "got to find something to do."

The two already loved basketball, and where they lived on campus there were "endless courts," so it was a match made in heaven.

"That really was the turning point for them as far as this is a sport we love," she said. "And then that became really fun because they played with the kids that were in middle school and high school, like as fifth graders. So that was a crazy experience."

Eventually, the family moved back to the United States and Mason and Gabe took part in AAU basketball, while also being coached by their father in high school.

"When you play for your dad as a coach, there's different expectations that are put upon you," Krenzelok said. "And they just both really wanted to succeed. But then I think there was an advantage to that, too. Like, a lot of kids aren't going to have access to a gym like they did because of having a dad who has keys, right?"

Mason said the "good outweighs the bad" when it came to having a dad as coach, and that it was an "experience we wouldn't trade for anything."

"It's definitely made us closer with our dad," he said.

"Looking back on it, it was an awesome experience," Gabe added. "But there were moments, too, where you're like — he coaches you harder because you're his sons or whatever. But I think that was early on, kind of, and then later on in our careers, in high school, I think I just was very appreciative to play for him. I think it's a big reason we are the way we are."

But some of that appreciation took some time to develop, the two said, while laughing through various experiences the trio shared on the court.

"Literally, one of our first freshman basketball practices in high school, I dropped the ball while he was talking — like, literally, I had it on my hip, and it just fell," Gabe recalled. "Kicks me out of practice. I'm like crying in the locker room two days into freshman basketball. And then I was like, 'Dad, you've gotta, like, chill.'"

"I've definitely been thrown out of practice my fair share of times," Mason added.

Finishing at Utah

After sharing the court together in AAU ball and high school, the two Madsen brothers committed to play collegiately at Cincinnati, where they hoped to continue that strong connection. But Gabe didn't feel the connection with the Bearcats and eventually transferred after his first season to Utah.

Mason stuck around for another year before eventually transferring to Boston College, where he expected to finish out his college career. Outside of Utah and Boston College meeting up in a postseason tournament, the two would likely never share the court again, especially as Gabe considered turning pro ahead of the 2024-25 season.

But as Gabe weighed the decision on whether to return to Utah or try his hand at the professional level, Mason was content at Boston College. Regardless of whether Gabe pursued a professional career, Mason had no desire to transfer again just to transfer.

"I'd been through the transfer process; I knew how hard that was," Mason said. "Him being here has made it easier, obviously, and I didn't know if I was going to pursue transferring if it wasn't to come play here. That was pretty much the only way I was going to leave. And there were some real conversations that were had, and very blunt conversations."

As Gabe weighed his options immediately following the team's NIT loss to Indiana State, Mason told his brother that he had "a good spot here" and it was "not something I'm just gonna give up." Mason met with his head coach at Boston College that same day and had "a really good meeting" about staying with the program.

"And so I left that meeting, and I told my girlfriend, I was like, 'I feel like I'm staying here,'" Mason recalled. "And then Gabe calls me that night, and he's like, 'Mason, we just landed. I had all this time to think.' He's like, 'I decided I'm leaving.' ... And then he's like, 'I'm just kidding, I'm coming back,' and he thinks it's this great thing.

"And I had told my girlfriend that I was coming back," he added. "And that, like, we're laughing now — that was not a great conversation. It was definitely, it was a trip, but obviously it worked out."

Gabe said it was a difficult decision, and one that he "definitely went back and forth a lot" on as he also tried to weigh what would be best for his brother, too.

"It was hard for him, because he knew if I was coming back, he wanted to come here," Gabe said, "but it's like a hard position to be waiting."

In the end, the two just wanted to be on the court together again as they ended their career.

"I think that the whole reason that I came out here was for this time now," Mason said. "And we got to practice together and whatnot, and so that was cool. But now to be in season, we're getting that closure that we never got. I think that's probably the most beautiful thing that came from this."

KANSAS

KANSAS BYU

BYU OKST

OKST UTAH

UTAH PURDUE

PURDUE MSU

MSU OKLA

OKLA FLA

FLA TEXA&M

TEXA&M MISSST

MISSST COLO

COLO IAST

IAST TXTCH

TXTCH TCU

TCU ILL

ILL WISC

WISC SETONH

SETONH MARQ

MARQ HOU

HOU ARIST

ARIST APSU

APSU BELLAR

BELLAR JAC

JAC FGCU

FGCU MIA-O

MIA-O EASTMI

EASTMI VILL

VILL UCONN

UCONN WESTGA

WESTGA NORTAL

NORTAL NOFLA

NOFLA STET

STET LIPS

LIPS EASTKY

EASTKY CENTMI

CENTMI OHIO

OHIO CENARK

CENARK QUEENC

QUEENC BALLST

BALLST TOLEDO

TOLEDO NIU

NIU AKRON

AKRON KENTST

KENTST BGSU

BGSU WESTMI

WESTMI BUFF

BUFF SYR

SYR PITT

PITT LY-IL

LY-IL DAV

DAV BUTLER

BUTLER XAVIER

XAVIER TENNST

TENNST TN-MAR

TN-MAR AF

AF WYO

WYO VATECH

VATECH BC

BC SCAR

SCAR LSU

LSU