Estimated read time: 5-6 minutes

- Five Utah teens were killed by peers from May to August.

- Violent incidents in Utah schools have increased significantly, with assaults tripling since 2018.

- A new juvenile justice program aims to intervene early and reduce student violence.

SANDY – When Jason Maldonado drove his son Kian to a football game in August and handed the teenager some cash, the moment turned unexpectedly tender.

The boy responded by saying, "That's what I love about you, Dad. You're always looking out for me."

Maldonado shed tears recently as he recalled the conversation from two months ago. It was the last time he saw his son alive.

Troubling trends

Kian Hamilton, 16, was stabbed that night and killed when he and several of his friends got into a fight with another group in a parking lot near Jordan High, police said. He is one of at least five teens killed in Salt Lake County during a four-month period from May to August, with police arresting boys as young as 15 for these deaths.

The tragedies coincide with an increase in reports of violent behavior across Utah's public schools and charters. The disturbing trend sent the KSL Investigators searching for solutions, and we found one program is showing promise across several Utah communities.

"We have definitely got to figure this out, so it never happens to anybody's kid," Maldonado said, describing his son as an easygoing boy and gifted athlete who planned to play baseball in college. "Something has to change." Three teens were killed during the same month as Kian, the youngest just 14 years old.

In May, a 16-year-old boy was stabbed on Herriman High's graduation day. And in July, a 17-year-old boy who police described as an "innocent bystander" was killed in a drive-by shooting.

Those deaths happened away from school property, but the state tracked a dramatic rise in violent incidents on campuses in the last six years.

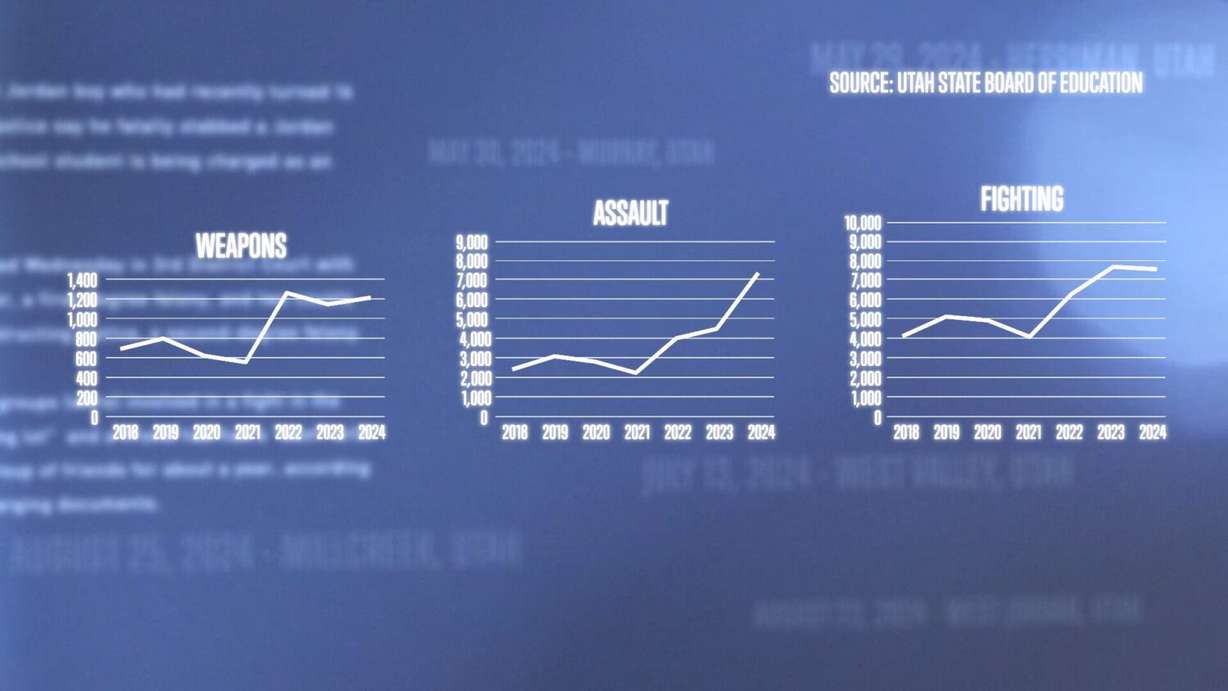

Examining data provided by the Utah State Board of Education, the KSL Investigators found reports of physical assaults shot up by 70% in the last year and have more than tripled since 2018 (from about 2,400 that year to 8,500 in 2024). Schools also recorded an increase in students having weapons and fighting on school grounds.

The Board of Education says improved data reporting may be one reason behind the increase. Whatever is driving the increase, officials overseeing juvenile justice initiatives in Utah hope a new program can help stop the trend in its tracks and encourage students to stay engaged in school – attending their classes, turning in their assignments, and staying involved in sports, drama, and other extracurriculars.

A push for prevention

Ginger Sanchez spent 15 years working at a juvenile detention center but now works in a different setting. She's at Kearns Junior High as the state's first mentor embedded at a school full time.

It's part of a pilot program through Utah's juvenile justice system, with the goal of intervening earlier if students start heading down a troubling path.

"It's better to stop a habit, rather than having to break a habit years later," Sanchez told KSL.

She emphasizes that she's not a disciplinarian. Instead, she offers support and guidance to kids and their families. Students get to choose if they work with her or not, but almost everyone she reaches out to decides to take her up on the offer. Then they spend time together working on managing emotions and figuring out what students need to succeed.

But it's not all work and no fun. Sanchez has plenty of incentives, including makeup, snacks and other goodies.

"Something that gets them excited," she said. "It doesn't matter what it is, as long as it keeps them motivated."

The program, run out of Utah's Juvenile Justice and Youth Services agency, also helps connect students and their parents to different resources like therapy and food assistance. It counts several mentors like Sanchez as part of an existing network throughout the state, but so far Granite and Ogden school districts are the only ones to have them embedded in schools.

The wider program is overwhelmingly successful, said Lori Butterfield, a supervisor with Utah's Juvenile Justice and Youth Services.

"Ninety-eight percent of the youth that complete our program successfully do not work their way further into the court system," Butterfield told KSL. "And that's huge. That's a big percentage."

Butterfield and Sanchez hope the program will expand – just one step to setting teens up for a positive future and turning the tide on student violence.

Changes in progress

Maldonado says he's all for school programs that help teens avoid violent behavior. But when students get hurt, he wants schools and police to do more.

In the two months since his son's death, Maldonado has pushed Canyons School District to make changes, including toughening its response to violence by students who are involved with gangs.

In response, the district has said it's increasing security and reviewing how it disciplines students. It's also in the process of hiring another administrator focused on addressing severe behavioral issues with students, said Canyons spokesperson Jeff Haney.

"Canyons District continues to improve facilities, reinforce emergency-response practices, and streamline the ways students and parents can request help with issues of harassment, bullying, or discrimination," Haney said in a statement.

Visiting a baseball field in Sandy where he and Kian, a third baseman, used to practice daily, Maldonado said memories of their conversations during those sessions – about friends, school and the future – flooded back.

"This was our little spot right here," Maldonado said. "It was our time just to be father and son."

While Kian was his stepson, Maldonado said the two were so close that they simply referred to each other as father and son.

Looking out at the field, he couldn't help but think about the life he wanted Kian to live.

"I wanted him to add to the world," Maldonado said. "And that's what he did. He added to the community."

This story is the first in a series. Thursday at 6 p.m. on KSL-TV, a second piece examines teenagers' access to weapons and what Utah authorities do and don't know about this disturbing trend.