Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

ATLANTA — Researchers have uncovered links between what came before the world's oldest writing system and the undeciphered designs left behind on engraved seals that were rolled across clay tablets about 6,000 years ago.

Scholars consider cuneiform the first writing system, and humans used its characters to inscribe ancient languages such as Sumerian on clay tablets beginning around 3400 B.C. The writing system is thought to have originated from Mesopotamia, now an area of modern-day Iraq.

Before cuneiform, however, there was a script using abstract pictographic signs called proto-cuneiform. It first appeared around 3350 to 3000 B.C. in the city of Uruk, in modern southern Iraq.

But the origins of proto-cuneiform's emergence have been murky, and many of its symbols remain undeciphered.

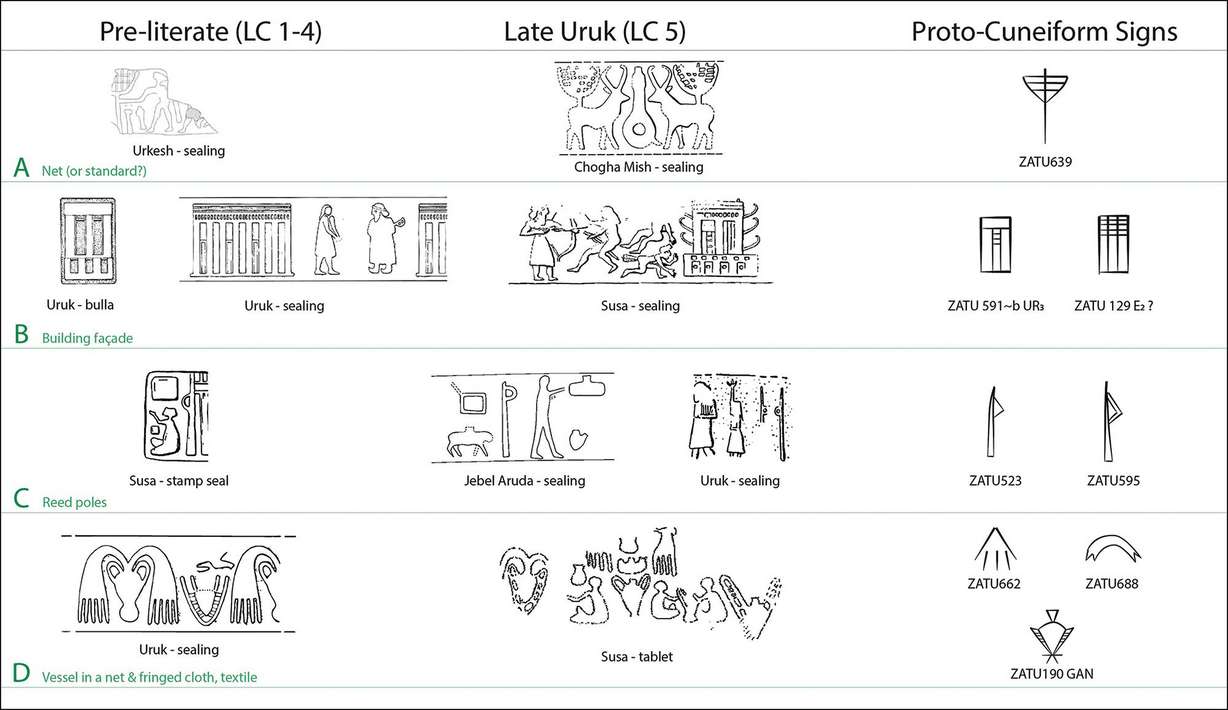

Researchers conducting a careful analysis of proto-cuneiform symbols were surprised to uncover similarities when they studied the engravings of seals invented in Uruk in 4400 B.C. and used to imprint on soft clay. Some of the symbols match exactly, and they also appear to convey the same meanings related to trade.

A study detailing the similarities was published Tuesday in the journal Antiquity.

"Our findings demonstrate that the designs engraved on cylinder seals are directly connected to the development of proto-cuneiform in southern Iraq," said lead study author Silvia Ferrara, a professor in the department of classical philology and Italian studies at the University of Bologna. "They also show how the meaning originally associated with these designs was integrated into a writing system."

From accounting to writing

Uruk, now known as Warka, was one of the earliest cities to arise in Mesopotamia, and it served as a center of cultural influence that could be traced from what is now southwest Iran to southeast Turkey.

Seal-cutters engraved designs on the cylinders, which could then be rolled across wet clay to transfer the motifs. A preliterate society widely used the seals in an early accounting system that helped track the production, storage and movement of crops.

"The close relationship between ancient sealing and the invention of writing in southwest Asia has long been (recognized), but the relationship between specific seal images and sign shapes has hardly been explored," Ferrara said. "This was our starting question: Did seal imagery contribute significantly to the invention of signs in the first writing in the region?"

The team compared motifs from the seals with proto-cuneiform pictographs. The researchers anticipated making small and indirect connections, but instead they identified seal images that directly connected to proto-cuneiform signs, suggesting that seals played a role in the developments that led to the birth of the first writing system, Ferrara said.

The images with the strongest connection related to the transport of jars and cloth, said study coauthor Kathryn Kelley, a research fellow in the department of classical philology and Italian studies at the University of Bologna.

"We focused on seal imagery that originated before the invention of writing, while continuing to develop into the proto-literate period," said Kelley and study co-author Mattia Cartolano, research fellow at the University of Bologna, in a joint statement. "This approach allowed us to identify a series of designs related to the transport of textiles and pottery, which later evolved into corresponding proto-cuneiform signs."

Deciphering unknown symbols

The more researchers uncover about ancient cities such as Uruk and the connections between the iconography ancient civilizations used, the more they may be able to decipher the hundreds of unknown proto-cuneiform pictographs, the study authors said.

"In view of the stylized and often abstract nature of many proto-cuneiform signs — a strong contrast with the much more picture-like Egyptian hieroglyphs — a full consensus on what these signs represent and where they originated will probably never be reached, but that does not mean one shouldn't try to explore the issue," said Eckart Frahm, the John M. Musser Professor of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at Yale University. Frahm was not involved in the study.

Writing seems like a necessary technology that would naturally develop over time, but it was only invented independently — without knowledge of the existence of writing — a few times in world history, Ferrara said.

"So, it has long been a question of interest what social and technological conditions encouraged the conceptual, cognitive leaps that resulted in written language," Ferrara said. "While the jury is still out on how much language coding the earliest phase of cuneiform actually has, importantly, it led to 'true' writing within a few centuries, so the invention of proto-cuneiform is a watershed."