Estimated read time: 2-3 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — When someone thinks of climate change, thoughts tend to shift toward electric cars and recycling. But what if improving climate change started with using bacteria?

While it's well-known that carbon dioxide is in the atmosphere, a lesser known danger that also resides in the atmosphere is methane, which has been determined to be a big culprit of global warming. Methane comes from natural habitats, like tundras and wetlands, as well as animals and humans, through burps and landfills.

Jessica Swanson, an assistant professor in chemistry at the University of Utah, said methane is 30 to 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide — which means there may be a solution in turning methane into carbon dioxide.

"If you think of taking a bunch of methane out there and turning it into (carbon dioxide), we immediately decrease (global) warming by 30 to 80 times," Swanson explained.

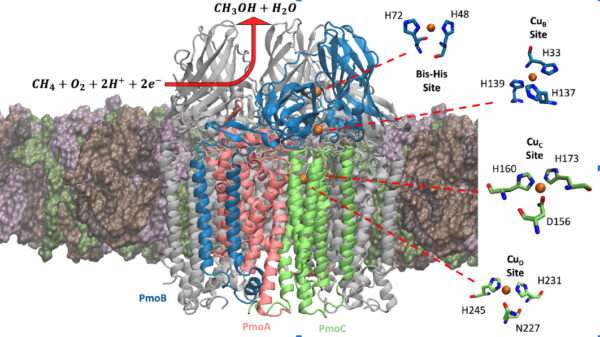

Swanson is currently researching ways to harness methanotrophs, a bacteria that can break down atmospheric methane into carbon dioxide and organic compounds.

One place Swanson said methanotrophs can be found is in wetlands. Bio matter, like dead trees, are broken down by methanogens, a bacteria that eat the matter and produce methane as a result. Methanogens don't need oxygen, so they can be found deep in decaying soils. Methanotrophs come along to eat the methane being produced, but methanotrophs need oxygen to survive, limiting how deeply they can go to eat the bacteria.

Because of the varying needs in oxygen, methane is more abundant and gets out faster than the methanotrophs can eat it, leading to the excess methane being released.

Swanson and her team plan to create reactors close to high-methane producing sites like landfills, where a lot of decay happens. If the team is able to secure funding and proper research for producing more methanotrophs, each reactor could potentially pull up to 280 metric tons out of the atmosphere per year, Swanson said.

Lumen Bioscience, a Seattle-based scientific research company, was awarded $1.5 million from the University of Utah in September for its work with preventing methanogens — archaea that emit methane — from entering the atmosphere through cow burps. Swanson's research with methanotrophs differs from Lumen's research in that while Lumen is striving to prevent methane from being emitted, Swanson is trying to get rid of the methane already out there.