Estimated read time: 5-6 minutes

SALT LAKE CITY — At the mouth of Dragon Canyon, ruins of a once-bustling mining town still remain.

The town — known as Silver City — was home to stores, hotels, restaurants, a post office and a saloon. Cowboy George Rust established the town in 1869 after discovering mines nearby. The town's economy centered around the mines, and at its onset, some tents, a saloon and a blacksmith shop compromised the majority of the area.

Silver City

"A History of Juab County" authored by Pearl D. Wilson tells the story well.

The silver mines proved fruitful. Residents built permanent establishments and homes. Though the town encountered difficulties with flooded mines and a 1902 fire, Jesse Knight built the Tintic Smelter. The town seemed to be on the up-and-up, but the smelter shut down after it couldn't compete with Salt Lake Valley operations. Knight built a mill, but that was lost to a fire. While Knight attempted to drain the flooded mines, it didn't pan out, and the population dwindled.

Soon railroad operations in Silver City ceased, and the town shuttered and became a ghost town.

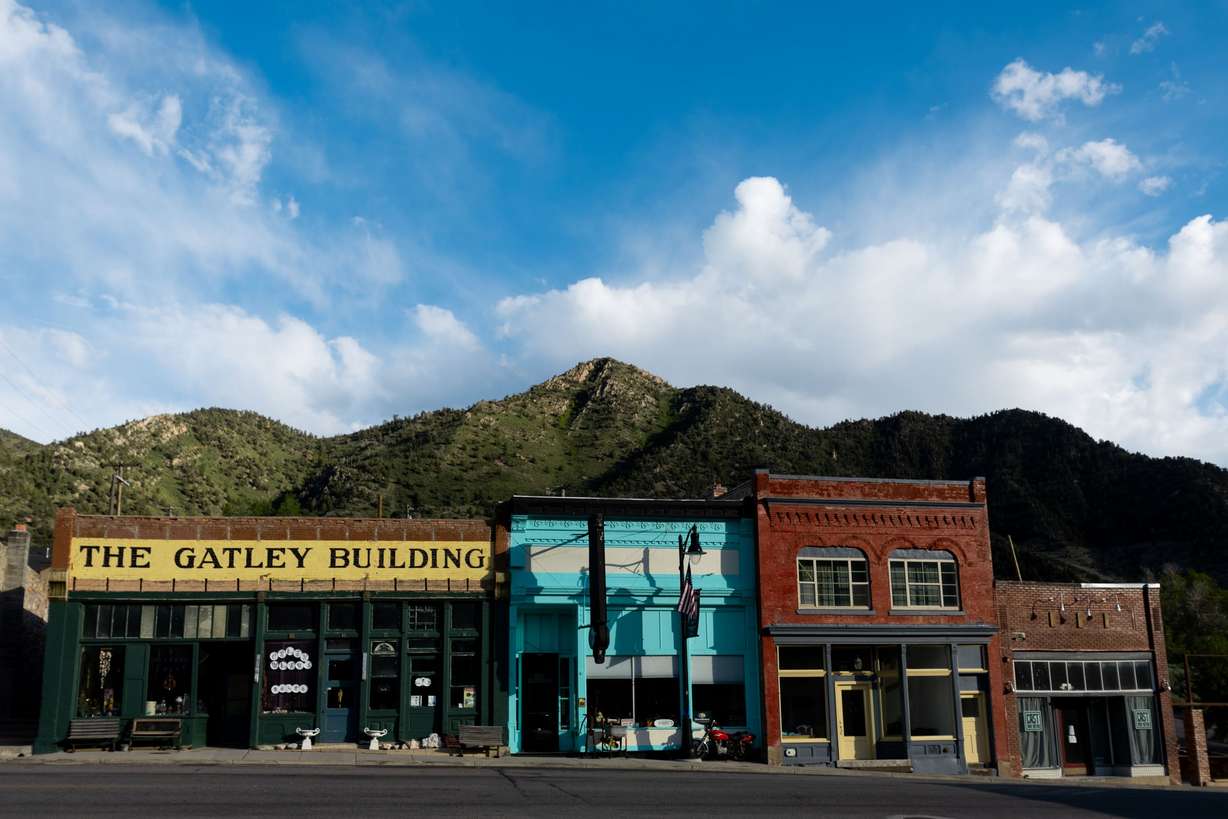

Today, nobody lives within Silver City's historic limits. Just a couple miles away, the city of Eureka is still populated. Around 700 people live in the town, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Though Eureka has survived to this day and its Main Street still has businesses and restaurants, other nearby towns, like Knightsville, had the same fate as Silver City.

Eureka differs from Silver City and Knightsville in that it's a historic town, not a ghost town. People still live in there, and you can visit by taking U.S. 6. Eureka residents can purchase groceries at a couple local stores, and if they need more substantial choices, they can drive to Santaquin. The town's home to three churches — Catholic, Methodist and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. There's also a local schooling system.

Spring City in Sanpete County is another example of a historic town that's not a ghost town. You have to drive a few miles off the highway to get there, but once you do, you'll be greeted by a historic district that looks frozen in time. There's a beautiful limestone Latter-day Saint chapel as well as a historic schoolhouse and bishop's storehouse. Residents live inside the town, and Main Street has a couple businesses you could frequent.

Ghost towns are different — they're abandoned or barren. Sometimes there may be a handful of residents who still live in the area, but the town itself is generally disincorporated. In the case of Silver City, all that remains are building foundations and a cemetery. In Utah, ghost towns generally once were places where mining or agriculture was booming, but something happened to them.

Mosida

The story is different for each town. Take Mosida as another example.

Mosida's relatively close to Silver City — it's in between Saratoga Springs and Elberta by Utah Lake. Today it's located on private property, and all that remains of the town is building foundations. The town was established in the 1910s and centered around grain and fruit trees. The Mosida Fruit Lands Company attracted workers and houses, and a school and a post office was built.

But the town was short-lived. The agriculture struggled, and the project of a town died out.

Though Mosida had a short history, the town of Thistle became a ghost town in recent history. Located in Spanish Fork Canyon, the town was established in 1878. It was a railroad town that swelled in population size as it became something of a train stop. The town had saloons, restaurants and a schoolhouse. It had hundreds of residents.

In 1983, residents scrambled to evacuate, as railroad workers and Utah officials saw an impending landslide.

The mountainscape crashed into the Spanish Fork River, and the town was flooded. Remains of the town are mostly submerged into the ground, and it's now known as a ghost town. Many Utahns still remember when this happened.

Grafton

These towns are mostly ruins at this point and don't look like the stereotype of a Western town. But the town of Grafton does.

If you've seen the movie "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid," then you've seen Grafton. It's near Zion National Park and has been used in other Western flicks as well. When Latter-day Saints came to southern Utah, they settled Grafton in 1859 with the intent of growing cotton.

Silt and flooding made it difficult for the residents to grow anything, and the population dwindled. By 1944, the remaining residents had left the town, and the site is preserved. Unlike ghost towns where only foundations remain, buildings are still upright and have been restored to how it's believed they would have originally looked.

Many of the aforementioned ghost towns had populations of only one or two thousand people at most, but not Frisco. It's just a few miles outside of Milford.

Frisco

Frisco is another ghost town that once was a mining town. Beehive-shaped stone kilns and abandoned buildings still remain — the vestige of a Wild West town. By 1885, it had attracted 6,000 people due to its wealth of copper, gold, lead, silver and zinc.

The streets were lined with saloons, and local writer Charles Knight called it "Dodge City, Tombstone, Sodom and Gomorrah, all rolled into one." Crime was rampant, to the point where a lawman only known as Marshal Pearson came into the town to clean it up.

"He allegedly told the lawless elements that he did not intend to make arrests," wrote Miriam B. Murphy. "Instead, he planned to shoot on sight anyone he saw breaking the law. He supposedly killed six outlaws on his first night in town."

These and other ghost towns in the state tell bits and pieces of Utah's wide ranging history. If you're looking for a summer activity to do with your family, consider visiting a ghost town.