Estimated read time: 7-8 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

- The McFarland family and conservationists preserved a former Utah monastery's land, resisting development.

- The land, once home to Trappist monks, is now thriving with sustainable farming and community activities.

- Efforts include organic farming, a revived woodshop, and wildlife preservation, honoring the monks' legacy.

HUNTSVILLE, Weber County — In the picturesque little valley just minutes from Ogden and the Wasatch Front, where Utah's rapid growth and development can be seen firsthand, one piece of land has resisted change.

Tucked in the Ogden Valley, land that was once home to Trappist monks — and is now their final resting place — has been preserved for future generations by a family who decided to resist the development moving across the valley.

The monks built the farm on clay-filled soil, turning it into fertile farmland. But the parcel of land the monks owned faced an uncertain fate after the monastery closed in 2017. Today, through the efforts of the McFarland family and local conservationists, this cherished landscape is not only preserved but thriving, connecting the past and future.

Post WWII monks sought refuge in Ogden Valley

In 1947, 32 Trappist monks seeking refuge after World War II settled in the Ogden Valley just outside of Huntsville. Arriving from the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani in Kentucky, they built the Abbey of Our Lady of the Holy Trinity as a sanctuary, grounded in faith and labor.

For more than 70 years, the monks worked with their hands to transform the fields into fertile farmland, cultivating hay, grain and potatoes. Bees produced creamed honey that put the monks' efforts on the map locally.

"Almost everyone in the Ogden Valley has memories of buying bread and honey from the monastery," says Jamila McFarland, a farmer who's now helping to manage and preserve the land.

Through their store, the monks offered not just goods but a sense of peace, forming deep bonds with the community. But as their numbers dwindled, the once-thriving monastery grew quiet. The fields they lovingly tended faced an uncertain future, leaving the community to wonder what would come next.

Closure and conservation

By 2017, the monks could no longer maintain their sprawling property. Their numbers had dwindled, with the youngest well into his 70s. Caring for the fields and the monastery had become a burden. Developers quickly saw an opportunity in the expansive acreage, proposing plans for mixed-use development that threatened to erase its history. Even the monastery's parent abbey in Kentucky considered development as a solution to offset the monastery's declining population and operational challenges.

Bill White, an area resident, recognized the significance of the land and the need to protect it. White purchased the property in 2016 for an undisclosed price, knowing the monastery faced inevitable closure. The monks, like White, were steadfast in their opposition to development on the land, advocating for the preservation of what they had nurtured for decades.

"The local monks have been against the (proposed) development from the beginning," White said in 2017.

Determined to honor their wishes, White collaborated with local land trusts to save the property. His vision involved reimbursing the purchase costs and establishing a conservation easement to safeguard the land permanently — a project estimated at $6 million. White's efforts ultimately secured an $8.8 million conservation easement, and now, the land remains protected from development.

New stewards, same spirit

When the monastery closed, the land seemed destined to lose its purpose. The monks' absence left behind not just fields and buildings but a void of meaning. That's when Kenny and Jamila McFarland stepped in, working in partnership with White to keep things running.

White, who did not have the agricultural experience to work the land on his own, sought capable stewards who could ensure the farm remained vibrant and productive. The McFarlands, a local farming family with a passion for sustainable agriculture, proved to be the perfect match.

"We visited initially to consult," Jamila McFarland recalls, "but as soon as we set foot here, we realized it was more than a business opportunity. The land had a unique spirit we couldn't ignore."

In 2022, the McFarlands began leasing the fields, taking on the day-to-day work of restoring the property while preserving its historical significance. They embraced organic farming practices, planting hay, wheat, onions, and pumpkins, like the monks before them. One of their standout initiatives, a pick-your-own pumpkin field, has drawn families from across the valley, reconnecting visitors with the rhythms of the earth and the joy of working the land.

The McFarlands' efforts didn't stop at farming. They launched a small on-site market to sell local produce and deepen the community's connection to the land. "It wasn't just about selling food," Jamila McFarland explains. "It was about ensuring the farm remained a place for people to gather, share, and celebrate its history."

A woodshop reborn

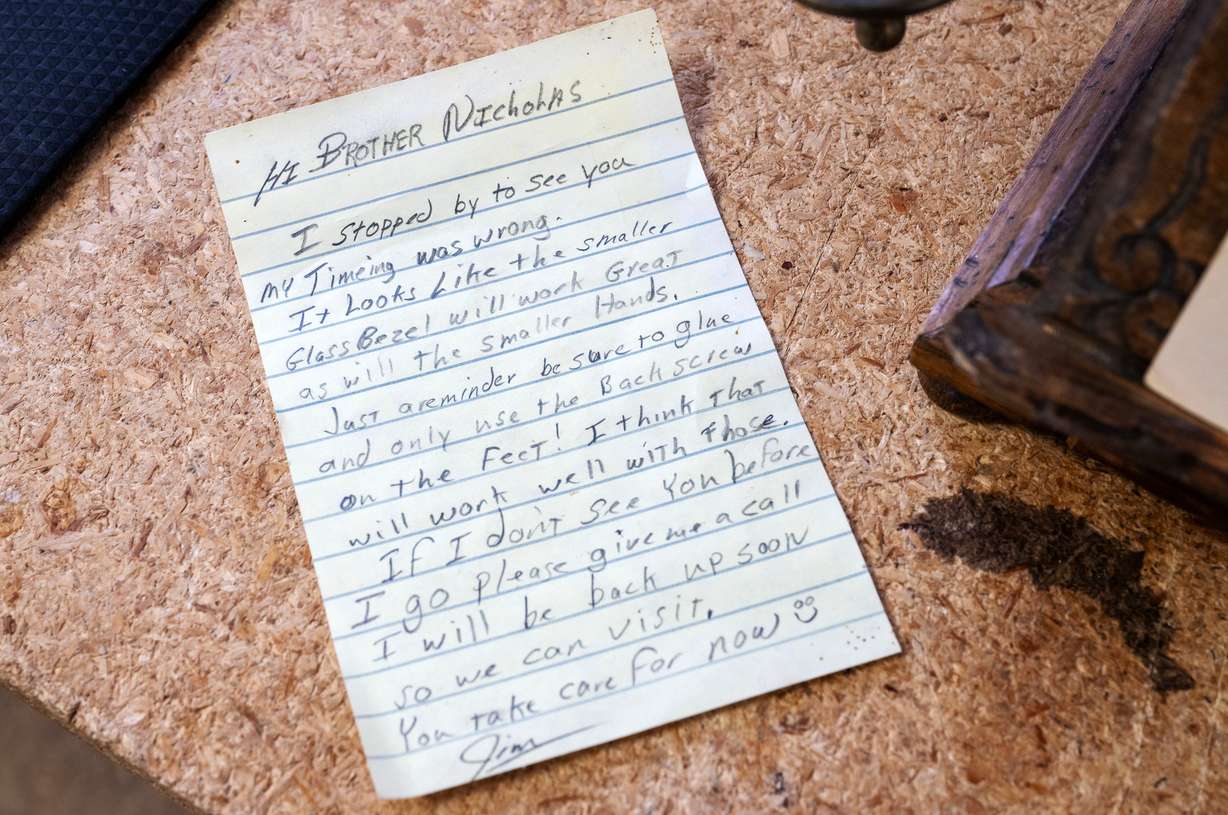

Tucked away on the grounds, the monastery woodshop stands as a reminder of a more analog time. Jack White, Bill White's son, recognized its significance the moment he stepped inside in 2016. Today, it's like the farm's former residents never left. An old monk's hat rests near the entryway, plans for the monastery's grounds are faded on blueprint paper dated "June 12, 1947," and hand tools hang meticulously on pegboard walls.

"When we got this property, there was a foot of sawdust all over the floor, and most of these tools weren't running anymore," White said. "We've been working for eight, nine years now, trying to make a real shop."

White and his friend set to work restoring aged machinery and salvaging what they could, honoring the craftsmanship of those who had worked there before. Soon, the hum of the monks' turning tools returned. Now, like before, the woodshop produces custom acoustic guitars and furniture, bridging the monks' past with the present.

"We're trying to keep something going here instead of just boxing it over and turning it into books," Jack White said. "It's about honoring the craftsmanship and spirit of those who came before us."

In reviving the woodshop, Jack White and his father aren't just preserving a building. They're safeguarding a legacy of mindfulness and manual artistry that is being lost more and more. The space is a living museum. It is not static but dynamic, still filled with the rhythm of the wood-turning machines and ongoing creation.

"There's definitely a magical feeling in here," Jack White muses. "Every time you walk out after working a while, you see big V's of geese flying over, cranes in the field, three kittens wandering around. It's awesome."

Nature's sanctuary

Beyond the cultivated fields and the hum of the woodshop, the monastery farm extends into the Ogden Valley's rolling hills and open fields, where nature thrives. Elk descend at dusk, their silhouettes striking against the fading light. Sandhill cranes wade through wetter parts of the land, picking for worms and other food. Occasionally, owls hoot from treetops, and foxes slip through the underbrush with quiet grace.

"There's so much wildlife on the farm," Jamila McFarland says, scanning the horizon. "You can hear the elk bugling at night. It's so neat."

The farm acts as a wildlife corridor in the area, a dwindling amenity for animals amid the encroaching development elsewhere in the valley. By maintaining organic practices and avoiding harsh chemicals, the McFarlands honor the monks' legacy of respect for the earth. As more and more plots of land are bought and more dwellings are built in the area, it's a chance to witness harmony between human activity and nature.

A vision for the future

The McFarlands aim to expand community programs like educational workshops, farm-to-table events, and partnerships with local schools to deepen people's connection to the land. Their overarching goal is not just preserving the land but also nurturing the values it represents. Respect for nature, commitment to community, and a sense of stewardship form the foundation of their plans.

"We feel there's a reason we should be farming the land," McFarland said. "The monks may have left, but their spirit is still here."

Progress doesn't necessitate erasure; it can embrace heritage and inform the paths we forge ahead. As McFarland said, while their physical presence is gone, the echoes of the monks' prayers mingle with the wind through the farm. It's a quiet song of continuity, carried forward by those who choose to listen.

Correction: The main photo caption previously had an incorrect first name. That has been updated.