Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

ARCO, Idaho — Far out in the eastern Idaho desert, we explored a canal just feet off the road, filled with thousands of rusted medicine bottles, hand-painted mugs, fine china, original glass soda bottles, children's toys and even a bird cage.

We walked past beer bottles, antique light fixtures, tin cans, rusted-over handheld mirrors and washboards that have been resting here for over 80 years.

Men, women and children lived here during World War II and the momentous events that marked the conflict, such as the Holocaust and the dropping of the atomic bombs in Japan.

Today, we can learn a little about their lives because this pile of trash has remained virtually untouched for all those years.

But why is a World War II trash heap in the middle of the Idaho desert? And what does a mile-long pile of trash have to do with the history of nuclear power in Idaho?

For that, let's go back in time.

It's the early 1940s, and tensions are quickly building toward World War II. The U.S. Navy is anxious to build support facilities to train sailors, build and test weapons, and be war-ready.

According to Susan M. Stacy's book "Proving the Principle," which details the history of the Idaho National Laboratory, the Navy needed an inland area with lots of space and flat enough land to transport large weapons.

"The Pacific Fleet needed a location fairly close to the West Coast where they could have their gun barrels realigned and basically refurbished because they could only last so many rounds of ammunition being fired through them," says Jon Grams, a project researcher for the Gateway for Accelerated Innovation in Nuclear at Idaho National Laboratory. "So in Pocatello, they built what they called the Pocatello Naval Ordnance Plant."

The Naval Ordnance Plant opened in Pocatello on April 1, 1942. The area was already home to the largest Union Pacific Railroad terminals in the U.S. and was on a transcontinental highway.

"The guns came from such fighting ships as USS Missouri and USS Wisconsin, whose revolving armored turrets, studded with 16-inch guns, the Navy's most powerful, helped win the Pacific war," says Stacy. "Repeated firing of the guns eroded the bore, wore out the rifling, and compromised the accuracy of the gun."

To fix them, the Pocatello plant removed the worn-out inner sleeves of the gun barrels and relined them with fresh metal.

Eventually, the Navy realized it needed somewhere to ship these weapons to for testing – again, somewhere large and flat. This is what they found in Arco, 65 miles from the Pocatello Naval Ordnance Plant.

The Arco Naval Proving Grounds

"They had this huge 900-square-mile open area here between mountain ranges on the east and west," says Grams. "And this is where they decided to set up a naval facility for test firing these guns."

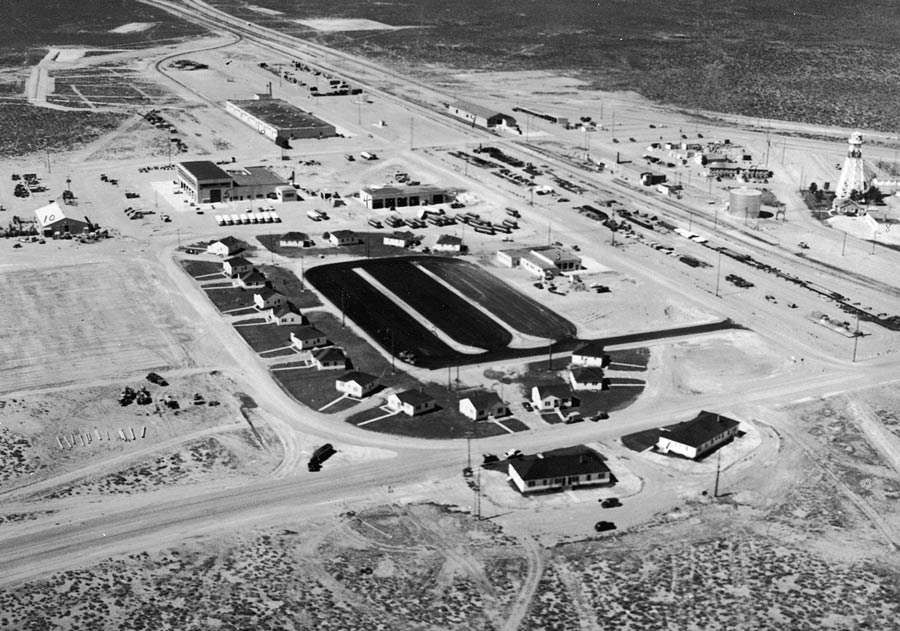

The 9-mile-wide, 36-mile-long Arco Naval Proving Ground was established in 1942. It was there Navy families lived, worked and thrived, just a few hundred feet away from where weapons were being tested during World War II.

With families living on the proving grounds, the Navy divided the area into residential and proof areas.

The residential area housed families. Marines organized baseball teams, and women engaged in sewing circles. Adults made sure to entertain the community with twice-weekly movie nights.

"On the other side of the railroad tracks, there used to be a locomotive shed," says Libby Cook, an architectural historian at Idaho National Laboratory. "They would pull the locomotive out, drop down a screen, put benches in, and folks could watch brand-new movies."

Eventually, the town was given its own name — "Scoville," after Cmdr. John A. Scoville, the officer in charge of the construction of the Pocatello plant and the proving ground.

"The Navy built for permanence, planting the grounds with trees and shrubs. The northernmost dwelling, the one with a matching garage, was reserved for the commanding officer," says Stacy. "Beyond the barracks were a kennel for the Marines' patrol dogs and a well-supplied commissary, which the civilians called 'the store.'"

The children in town were as normal as could be, going to school, playing by the water tower, and even getting scolded by the Marines when they acted out.

"Students filled up a gun-metal-gray bus and went to school at Arco 17 miles away, sometimes accompanied by a Marine when certain boys got out of hand," says Stacy. "In typical military fashion, the bus stopped one day each year in front of the Marine barracks, where no child could escape the dreaded 'tick shot,' a booster to prevent Rocky Mountain spotted fever."

Overall, life was normal, with a plethora of families living in close quarters.

"There's a great photo of a woman named Pat Gibson with her horse. They had livestock and animals out here," says Cook. "We have another family who kept a small dairy herd just north of the Naval Proving Ground, and they would provide milk to the families in town."