Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Oh, the places you’ll go.

Each year for more than a century, state wildlife biologists place metal bands on various ducks, geese and swans with the purpose of tracking migration patterns. Now, a new comprehensive website allows anyone to see where those birds went after they were tagged — and there are some interesting places.

The Utah Division of Wildlife Resources launched Utah’s Waterfowl Band Returns Tuesday. The website features data collected from thousands of waterfowl — including the American wigeon, Canada goose, cinnamon teal, Gadwall, green-winged teal, mallard, northern pintail, and redhead duck — that have been tagged by state biologists over time.

In fact, the website features the tracking of where more than 200,000 waterfowl went since the agency began banding the birds in 1912.

"We've tracked waterfowl — ducks, geese, swans — in the state for many, many years now and we've never really shared that data much with the public because there really wasn't a great platform to do that," said Blair Stringham, DWR's migratory game bird program coordinator. "Now that we've got all these cool mapping tools and visual displays and stuff, we're able to show that data in a way that actually makes sense to people rather than numbers on a page."

Here’s how the banding works. Once a bird is tagged, the band number is kept on record. The band notes what species the bird is and when and where the bird was tagged. After a tagged bird is either recaptured, found dead or killed, biologists or anyone else who recovers a tagged bird can report the bird’s band number, the location it was found, and the date it was recovered to the U.S. Geological Survey Bird Banding Laboratory website. Once that data is collected, Utah biologists can see where the bird ended up.

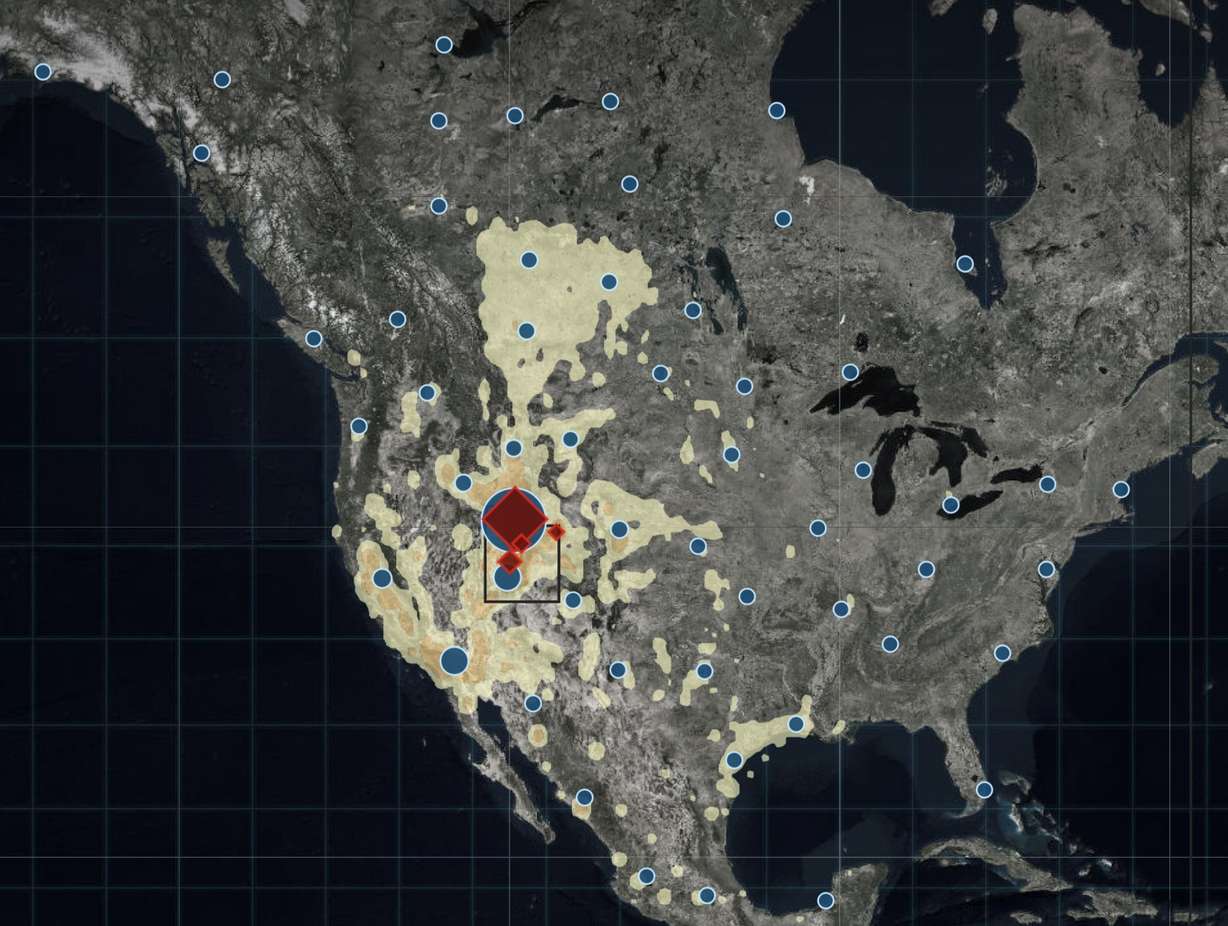

The website then plugs in the geotags from where the bird was tagged and where it was later found. According to the new website, most birds tagged in Utah migrate across the intermountain west to California or the western Gulf Coast.

They also frequently end up in northern Canada. However, some of the birds banded in Utah have been found in incredible places outside of North America. For example, one northern pintail banded in Box Elder County in 1942 was found by scientists at the Palmyra Atoll National Wildlife Refuge — a small atoll in the Pacific Ocean south of Hawaii.

Another northern pintail banded in Box Elder County 28 years later was hunted down near the shore of the East Siberian Sea in northeastern Russia in 1971. One cinnamon teal tagged in Davis County back in 1965 was later hunted in Colombia.

Stringham explained that biologists knew there were some outliers in migration patterns, and some of the outlier spots weren't a big surprise, especially since birds are so mobile.

"But some of the places they show up like Russia or that spot out in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, you still have to scratch your head sometimes and wonder how did that happen exactly?"

The website is similar to PeliTrack, which the state agency launched in 2018. That website allows people to track banded pelicans to see where they migrate, and has also yielded interesting results. As of Tuesday, the state’s three main tracked pelicans — Aurora, Cassandra and Penelope — were spotted in eastern Utah, Arizona and southern Mexico.

While there are hundreds of thousands of birds that have been tracked over time, wildlife officials point out there are millions of birds that travel through Utah during annual migration patterns. The data collected over time from banding is a sample size that helps biologists learn more about bird species migration patterns and thus helps state and federal officials make their waterfowl management policies.

"It really started years ago to answer questions of — we see ducks here for a little while and then they're gone. Where did they come from and where are they headed? People started putting those metal leg bands on their legs to try to learn that and through that data, we've learned there are basically four migration routes throughout North America," Stringham said. "We've got a big enough dataset now where we really can start to answer some of those questions. We can see where a lot of the birds that move through the state are coming from and where they're spending significant amounts of time."

He added he expects the website will be updated as more birds are tagged and more tag numbers are returned to state wildlife biologists in the future.