Estimated read time: 7-8 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

Editor’s note: This is the first part of a series looking back at the history and impact of the transcontinental railroad, which was completed 150 years ago this year.

SALT LAKE CITY — The accounts vary as to exactly how many people attended the merging of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads at Promontory Summit in northern Utah on May 10, 1869, but the National Park Service estimates approximately 300 to 1,500 people were there for that moment.

There, a ceremonial golden spike was — as Patricia LaBounty, curator of the Union Pacific Railroad Museum describes — symbolically “gently tapped” into the ground to connect the two lines and merge the east and west together for the first time. It signaled one of the grandest achievements in American transportation history had just been accomplished.

However, the race to get there was wild in its own right, and that work is the theme of a traveling exhibit set to open Friday at the Utah Museum of Fine Art. The exhibit, “The Race to Promontory: The Transcontinental Railroad and the American West” highlights the work of photographers Andrew Joseph Russell and Alfred A. Hart, as they documented the mad rush to construct a transcontinental railway from their time photographing it: 1866 to 1869.

In a way, the exhibit shows how the budding railroad and photography fields intertwined for the first time.

Russell and Hart’s work has remained within the Union Pacific Historic Collection and was recently on display in Omaha, Nebraska. It will be on display in Sacramento, California, this summer as well. The exhibit at the UMFA also includes works from Utah photographer Charles Savage and includes the actual golden spike on display, along with the Nevada and Arizona silver spikes that were displayed at the connection of the railways. It's the first time all three spikes have been in Utah together at once since 1869.

“We’re really fortunate to be able to celebrate the sesquicentennial in this way with original works of art, the original photographs from the Union Pacific Railroad Museum, as well as important historic artifacts,” said Leslie Anderson, curator of European, American, and regional art at UMFA. “It makes you think about the various choices that these particular photographers — who were artists — made in composing their scenes.”

A race toward history

This story truly began in 1862. While proposals had been made for a transcontinental railroad line as early as the 1840s, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act into law on July 1, 1862 — at a time the U.S. was in the middle of the Civil War.

The bill gave land grants and bonds to the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroad companies for building a transcontinental railroad between the American Midwest and the Pacific coast. That, in turn, set off a race that changed history.

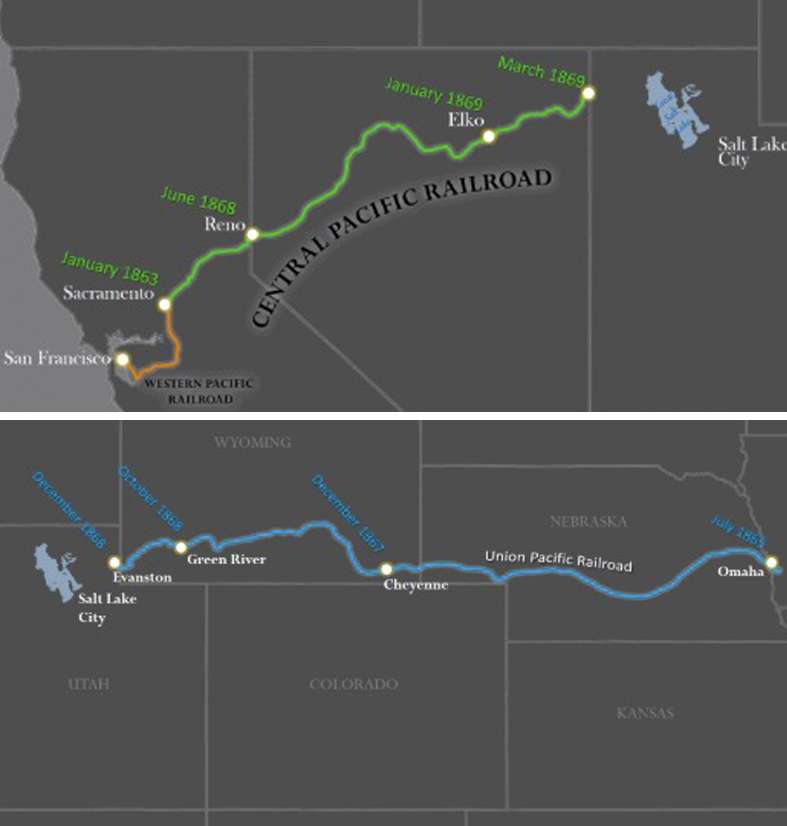

Central Pacific began working eastward out of Sacramento in January 1863, but the work was slow. The company didn’t reach Reno, Nevada, until summer 1868 because of the difficulties from the Sierra Nevada Mountains, according to Utah State History. Once they got to Reno, the pace picked up. The company made it through Nevada to the northwest Utah border by March 1869.

Union Pacific, on the other hand, went westward instead and moved more ground quickly because workers only had to worry about the Great Plains. The work began out of Council Bluffs, Iowa, in July 1865 and workers were in southwestern Wyoming about the same time Central Pacific reached Reno. Union Pacific made it to northeastern Utah by December 1868, Utah State History noted.

While the Golden Spike was driven on May 10, 1869, the rail lines could have been connected sooner had there not been a squabble over Utah. Both companies lobbied Congress to build the line through Utah and extend the $48,000 in government bonds for each mile of track laid down.

So the lines passed each other until Congress settled the matter on April 9, 1869, where it named Promontory Summit the place the two lines would meet, according to a history compiled by the National Park Service.

As the date the lines would meet neared, the two sides kept their rivalry interesting. A $10,000 bet was made after Central Pacific officials boasted their workers could lay down 10 miles of track in one day. The workers accomplished that in less than 12 hours to win the bet on April 28, 1869, according to Utah State History.

Two weeks later, the two lines officially merged at Promontory Summit.

Capturing the race

In many ways, the transcontinental railroad was the first story widely covered as it happened because of the telegraph lines built at the same time as the railroad lines.

“This was the first nationally broadcast media event in our nation’s history,” LaBounty said. “At Promontory Summit on that historic day, there was a wire attached to one of the ceremonial spikes. There was a telegrapher present who had a special wire to the transcontinental telegraph line.”

As the final spike went into the ground ceremoniously, that telegrapher tapped the official message to the nation that the work was completed. Instead of a whole message, LaBounty said that telegrapher sent back four letters to the nation: “D-O-N-E.”

However, the creation of this railroad line that connected the country together also happened about the same time photography began to blossom. Russell, who documented the Civil War prior to this project, and Hart’s work give context to the fierce work that had to be completed for history to be made.

Savage joined Russell as the rail work reached Utah and their photos show how crews tamed the state’s rugged mountainous terrain — much like the Central Pacific workers had dealt with in California.

Russell ended up capturing the most famous image of the project. On the completion date, May 10, 1869, he took the photo known as “East and West Shaking Hands.” The original version of that photo is hanged adjacently to the three spikes as a part of the exhibit. However, as LaBonty points out, it’s not the first photo of the merger celebration. That photo plate was destroyed earlier in the day and Russell rushed to recreate the image.

“Just after exposing that photograph, that plate broke at the site,” LaBounty said, pointing at the iconic image. “It was never really intended to be the photo, but because it survived this is, of course, the common photograph.”

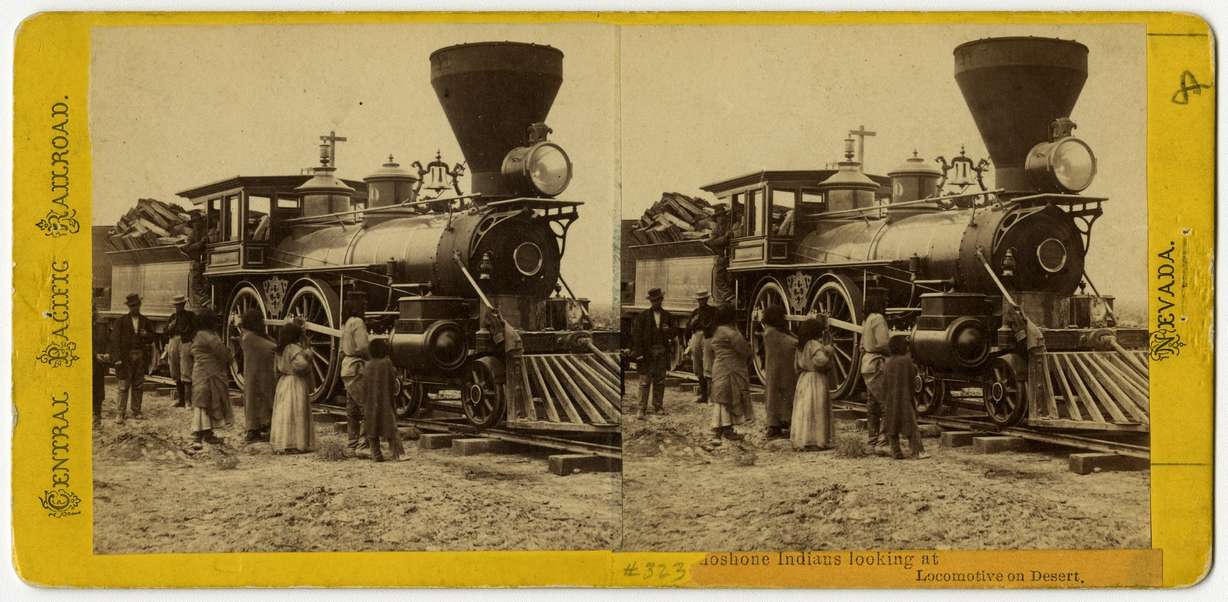

More than 15,000 Chinese workers and thousands of other workers — such as Irishmen and even Mormon settlers as the work reached Utah — labored through difficult weather and tough terrain to create the rail lines. It wasn’t just laying down track, either. In some cases, they had to build bridges and steep grades for the rail line to work. In all, the scenes captured show the difficult work that had to be done to build the transcontinental line.

It’s not just the work of the rail lines that is impressive. The exhibit also highlights the vast skill of the photographers of the era who truly pioneered the artform, as well. The three photographers’ work showcased the American West’s beautiful vistas and scenery long before Ansel Adams made it a popular art form.

Anderson explained the photographers in the exhibit used “wet plate” photography, which was invented in the 1850s. This process allowed a lot of artistic freedom and also allowed those who used it in the 1860s to send to newspapers quickly.

“I would describe (the exhibit) as the result of experiments of very adventurous artists,” she said. “Russell and Hart were painters before they took up photography and they were attracted to it because of its (scene) veracity — it looks like a document, right? But they are able to manipulate what is shown for the audience.”

The exhibit runs through May 26 and includes various speaker events, as well as other activities throughout its span. The three spikes will remain at the center until April when the golden and Nevada spikes will travel to the Utah Capitol to be on display. Tickets, hours and pricing can be found at UMFA’s website.